This is an on-going serialisation we are doing of a great little book called, ‘A history of community asset ownership’ by Steve Wyler who has kindly agreed for us to reprint his book on our website. We think a much better title for the book would be ‘The UK common peoples history’. We at Permanent Culture Now were going to do a very similar take on History that Steve has done with his book, so when we saw it we were like that’s great someone has already done the hard work. So we are expanding the work by adding our views as to why this history is relevant for today, drawing parallels with then and now and taking from it inspiration for building a more permanent culture. You can find out more about development trusts here.

Peoples History part 2: Desolation and wilderness

Time and time again people rose in rebellion against the injustice of land enclosures. In 1513 a turner in a fool’s coat wandered through the City of London calling for shovels and spades, and Londoners threw down enclosures around the city. In 1516 Thomas More’s Utopia castigated the wealthy for the misery caused by enclosure of land, and renewed the demand for all property to be held in common. In 1549 the largest popular uprising of all took place in Norfolk where Robert Kett and 15,000 rebels assembled on Mousehold Common outside Norwich, and drew up a manifesto for justice and community ownership.

Shovels and spades

After the failure of the Peasants’ Revolt, the encroachment by merchants and nobility upon commonly owned land continued, creating bands of landless workers and widespread vagrancy, and generating discontent and further outbreaks of rebellion. Occasionally there were small and temporary victories, for example in London in 1513, as Edward Hall’s Chronicle records:

After the failure of the Peasants’ Revolt, the encroachment by merchants and nobility upon commonly owned land continued, creating bands of landless workers and widespread vagrancy, and generating discontent and further outbreaks of rebellion. Occasionally there were small and temporary victories, for example in London in 1513, as Edward Hall’s Chronicle records:

… the inhabitants of the towns about London, as Iseldon [Islington], Hoxton, Shoreditch, and others, had so enclosed the common fields with hedges and ditches, that neither the young men of the city might shoot, nor the ancient persons walk for their pleasures in those fields, but that either their bows and arrows were taken away or broken, or the honest persons arrested or indicted; saying ‘that no Londoner ought to go out of the city, but in the highways.’

This saying so grieved the Londoners, that suddenly this year a great number of the city assembled themselves in a morning, and a turner in a fool’s coat, came crying through the city, ‘Shovels and spades! Shovels and spades!’ So many of the people followed that it was a wonder to behold. And within a short space, all the hedges about the city were cast down, and the ditches filled up, and everything made plain, such was the diligence of these workmen.(2)

The King demanded an explanation. The authorities complained of the ‘injury and annoying’ done by the protesters to the landowners, but King’s council after some deliberation decided not to take action, ‘after which time these fields were never hedged’.

Thomas More’s Utopia

The English humanism which flourished in the 1500s cast fresh eyes on fundamental questions of human behaviour and social organisation, and among the most prominent of this generation of philosophers and scientists was Thomas More. In 1516 he wrote his famous work, Utopia, in which he denounced the injustice of land enclosures:

The English humanism which flourished in the 1500s cast fresh eyes on fundamental questions of human behaviour and social organisation, and among the most prominent of this generation of philosophers and scientists was Thomas More. In 1516 he wrote his famous work, Utopia, in which he denounced the injustice of land enclosures:

They enclose all in pastures; they throw down houses; they pluck down towns; and leave nothing standing but only the church, to make of it a sheep-house. And, as though you lost no small quantity of ground by forests; chases, lands and parks; these good holy men turn all dwelling places and all glebeland into desolation and wilderness.

Therefore, that one covetous and insatiable cormorant and very plague of his native country may compass about and enclose many thousand acres of ground together within one pale or hedge, the husbandmen be thrust out of their own…

All their household stuff, which is very little worth, though it might well abide the sale, yet being suddenly thrust out, they be constrained to sell it for a thing of nought. And when they have, wandering about, soon spent that, what can they else do but steal, and then justly, God wot, be hanged, or else go about abegging? And yet then also they be cast in prison as vagabonds, because they go about and work not; whom no man will set a work, though they never so willingly offer themselves thereto.

The poor are more worthy

Thomas More claimed that the poor were more worthy to enjoy goods and property than the rich ‘because the rich men be covetous, crafty, and unprofitable: on the other part, the poor be lowly, simple, and by their daily labour more profitable to the common wealth than to themselves.’ More believed that individual property ownership was a great cause of distress, and in Utopia would be abolished:

Setting all upon a level was the only way to make a nation happy, which cannot be obtained so long as there is property: for when every man draws to himself all that he can compass, by one title or another, it must needs follow, that how plentiful so ever a nation may be, yet a few dividing the wealth of it among themselves, the rest must fall into indigence.

A utopian society

The society proposed in Utopia was ruled by a Prince and had many authoritarian features. Order and discipline were more important than liberty, and for women especially this was no earthly paradise. But there was religious tolerance, and private possessions were not allowed. Everyone (men and women) would work for only six hours a day, and everyone would learn a particular skill:

Besides agriculture, which is so common to them all, every man has some peculiar trade to which he applies himself, such as the manufacture of wool, or flax, masonry, smith’s work, or carpenter’s work.

One feature of Utopia, which featured in many later community experiments, was that everyone had the option to eat communally, but was not compelled to do so:

Though any that will may eat at home, yet none does it willingly, since it is both ridiculous and foolish for any to give themselves the trouble to make ready an ill dinner at home, when there is a much more plentiful one made ready for him so near hand Thomas More later became Lord Chancellor, fell out with Henry VIII, and was executed, but Utopia remained as a beacon for radical dissent for three centuries.

Robert Kett and the rebellion of the commons

The greatest popular rebellion against the illegal land enclosures took place in 1549, and started when villagers in Wymondham in Norfolk held a festival to commemorate Thomas a Becket. The festival was itself an act of defiance, for as everyone knew, Becket was a saint and had been murdered by the henchmen of a king. Indeed, the villagers had good reason to be angry. The local landowners were fencing in open fields on which the villagers depended for their livelihood. Deprived of common land for crops and grazing and fuel, and with no means to seek justice in the courts, the peasants had grown desperate.

The greatest popular rebellion against the illegal land enclosures took place in 1549, and started when villagers in Wymondham in Norfolk held a festival to commemorate Thomas a Becket. The festival was itself an act of defiance, for as everyone knew, Becket was a saint and had been murdered by the henchmen of a king. Indeed, the villagers had good reason to be angry. The local landowners were fencing in open fields on which the villagers depended for their livelihood. Deprived of common land for crops and grazing and fuel, and with no means to seek justice in the courts, the peasants had grown desperate.

Landowner Kett joins the rebellion

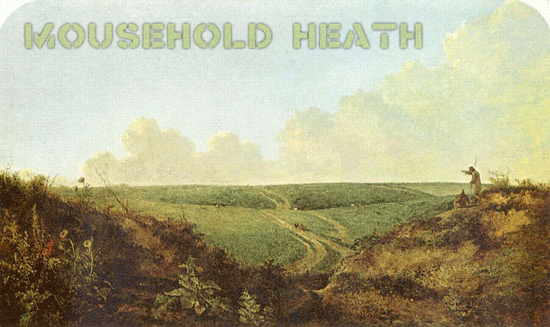

On that summer’s day they marched towards the estate of John Flowerdew, a notorious landowner. Flowerdew was clever and bribed the crowd not to tear down his fences, but rather to tear down the fences of a neighbour he disliked, Robert Kett. So the mob marched in that direction. Then something unexpected happened. When he heard their grievances, Kett listened and joined them, even helping to tear down his own fences. Indeed he became their leader. On 9 July 1549 Kett led the crowd to Norwich, at that time the second city of the kingdom. The gates were barred, so they set up camp below the city walls, on Mousehold Heath. In a few days, over 15,000 people had gathered. They tore down enclosures around the city. The Mayor of Norwich offered bribes and pardons for the crowd to disperse, but the people rejected all offers; they were determined to settle for nothing less than justice itself, determined not to ‘endure such great shame, as, living out our days under such inconveniences, we should leave the Commonwealth unto our posterity, mourning and miserable, and much worse than we received it of our fathers.’

They believed that if they gave way, oppression would gather pace: ‘Shall they, as they have brought hedges against common pastures, inclose with their intolerable lusts also, all the commodities and please of this life, which Nature the parent of us all, would have common, and bringeth forth every day for us, as well as for them?’

Under a spreading oak tree on Mousehold Heath, which they named the Oak of Reformation, Kett and his council of rebel leaders met. From here they controlled the great crowd, ensuring supplies of provisions and keeping order. On 24th July the insurgents attacked the walled city, armed with nothing more than pitchforks, sticks and mud. After a fierce struggle they entered the city and took control.

The rebels believed that if the king would learn of their grievances, he would provide redress. After all, the tyrant Henry VIII was dead and his son, the boy Edward VI, was young and as yet uncorrupted. So under the Oak of Reformation the people drew up their demands:

We pray your grace that no lord of no manor shall common upon the Commons.

We pray your grace to take all liberty of let into your own hands whereby all men may quietly enjoy their commons with all profits.

We pray that all bond men may be made free for god made all free with his precious blood shedding.

We pray that Rivers may be free and common to all men for fishing and passage.

We pray that the poor mariners or Fisherman may have the whole profits of their fishings as purpres grampes whales or any great fish so it be not prejudicial to your grace.

We pray that it be not lawful to the lords of any manor to purchase land freely and to let them out again by copy of court roll to their great advaunchement and to the undoing of your poor subjects.

We pray that every proprietary parson or vicar having a benefice of £10 or more by year shall either by themselves or by some other person teach poor men’s children of their parish the book called the cathakysme and the primer.

Petitioning the King

The petition was sent down to London and the great crowd on Mousehold Heath waited for the answer. Eventually, the King and his Protectors offered promises and pardons to appease the rebels, but at the same time they raised an army to hunt them down and destroy them. The first attack by 14,000 soldiers was beaten off. A second attack, led by the infamous Earl of Warwick, was a different matter. Three thousand rebels were slaughtered and thrown into a mass unmarked grave, the greatest ever massacre of English citizens by an English army. Robert Kett was captured a few days later, tortured, convicted of treason, and hung over the side of Norfolk Castle, as an example. Other rebels were treated in similar fashion. The branches of the Oak of Reformation were hung with bodies.

The petition was sent down to London and the great crowd on Mousehold Heath waited for the answer. Eventually, the King and his Protectors offered promises and pardons to appease the rebels, but at the same time they raised an army to hunt them down and destroy them. The first attack by 14,000 soldiers was beaten off. A second attack, led by the infamous Earl of Warwick, was a different matter. Three thousand rebels were slaughtered and thrown into a mass unmarked grave, the greatest ever massacre of English citizens by an English army. Robert Kett was captured a few days later, tortured, convicted of treason, and hung over the side of Norfolk Castle, as an example. Other rebels were treated in similar fashion. The branches of the Oak of Reformation were hung with bodies.

History is a tale told by the victorious

Contemporary accounts are all but silent about this uprising against the theft of common land. There was no monument to mark the rebellion, no gravestones to show where the dead lay buried. It was as if it had never happened.

The story of Kett was not revived until two hundred and fifty years later, when as we shall see, Thomas Spence and Tom Paine were proclaiming that the theft of the commons from the people was the root cause of poverty in the new industrial age. By the 1790s Mousehold Heath, the site of the rebellion, had itself fallen victim to enclosures by wealthy landowners, and by then enclosures were legalised by Acts of Parliament. In the 1800s paintings of Mousehold Heath appeared by John Crome and John Sell Cotman. In these paintings the heath remains unenclosed. Paths, open to all, wander though a lovely wilderness, under wide skies. Here is a celebration of the world Kett’s rebels fought for, a freedom, once cherished, now forever lost.

A few years later John Clare, the peasant poet, wrote:

Unbounded freedom ruled the wandering scene;

No fence of ownership crept in between

To hide the prospect from the gazing eye;

Its only bondage was the circling sky.

A mighty flat, undwarfed by bush and tree,

Spread its faint shadow of immensity,

And lost itself, which seemed to eke its bounds

In the blue mist the horizon’s edge surrounds.

Now this sweet vision of my boyish hours,

Free as spring clods and wild as forest flowers,

Is faded all – a hope that blossomed free,

And hath been once as it no more shall be.

Enclosure came, and trampled on the grave Of labour’s rights, and left the poor a slave.

Fence meeting fence in owner’s little bounds

Of field and meadow, large as garden-grounds,

In little parcels little minds to please,

With men and flocks imprisoned, ill at ease.

Each little tyrant with his little sign

Shows where man claims earth glows no more divine;

But paths to freedom and to childhood dear

A board sticks up to notice ‘no road here’.

(The Moors, c 1824-25)

Forgotten again for a century and more, much of Mousehold Heath was submerged within the expanding suburbs of the city of Norwich. In the 1960s, the municipal masters of Norwich cut down the Oak of Reformation, to make way for a car park.

Relevance for a permanent culture now

Enclosures

On a basic and primary level History tells and informs us of events in our past, with particular reference to this piece our past history tells us that the enclosure of land in our past is still very much a part of the present. Understanding the enclosures and commons as part of our history is a way provides us with a context of our struggle for the commons and for the end of enclosure as we know it, and since historical knowledge of the commons and enclosures is obscured and in some ways hidden from us, it only seems appropriate to try and provide awareness of these events and historical actions as a means of putting people in the historical picture. When nations rise up against their tyrannous governments, the uprising is made more prominent when it is backed up by an ongoing historical narrative of struggle, we hope that in our own small way that we can add to this body of knowledge and historical awareness.

Utopias

Utopia’s are as relevant today as they were in Thomas Moores time, with people seeking a better future through either revolutionary social change, new economic systems, peer to peer systems or reclaiming the commons. It is interesting to note that Utopian ideals have mainly focused on the distribution of resources as the tool to achieve change throughout history with the Thomas Moore arguing that the poor were more worthy to enjoy goods than the rich, to modern day Occupy movements questioning the one percent’s right to vast wealth and power. It seems that these battles have been with us a long time.

More Information

References:

2. Edward Hall, The Union of the Noble and Illustre Famelies of Lancastre and York, 1542.