This is an on-going serialisation we are doing of a great little book called, ‘A history of community asset ownership’ by Steve Wyler who has kindly agreed for us to reprint his book on our website. We think a much better title for the book would be ‘The UK common peoples history’. We at Permanent Culture Now were going to do a very similar take on History that Steve has done with his book, so when we saw it we were like that’s great someone has already done the hard work. So we are expanding the work by adding our views as to why this history is relevant for today, drawing parallels with then and now and taking from it inspiration for building a more permanent culture. You can download a pdf of the book for free here where you can also find out more about development trusts, this will not have our commentary in it, so please come back and check the expanded articles on our site.

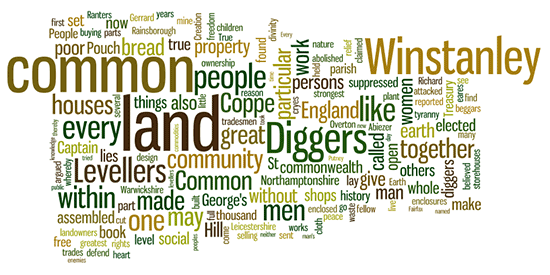

A common peoples history of the UK part 3: Levellers and ranters and diggers

Despite the failure of Kett’s rebellion, More’s assertion that ‘setting all upon a level was the only way to make a nation happy’ was not easily suppressed. In 1607 across the Midlands great crowds gathered, led by the mysterious ‘Captain Pouch’, to throw down the hated fences. In the 1640’s Levellers such as Richard Overton called for enclosed lands to be returned to the poor, and Ranters such as Abiezer Coppe kissed beggars in the street and cried out that that the day was fast approaching when all things would be held in common. In 1649 Gerrard Winstanley and a small band of Diggers occupied a patch of waste land on St George’s Hill in Surrey, to ‘work together, eat bread together’, in the belief that ‘the Earth ought to be a common Treasury to all’.

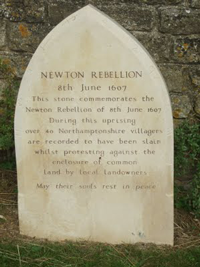

Captain Pouch

The story of Captain Pouch is found in the Annales of England, published in 1632:

The story of Captain Pouch is found in the Annales of England, published in 1632:

About the middle of this month of May 1607, a great number of common persons suddenly assembled themselves in Northamptonshire, and then others of a like nature assembled themselves in Warwickshire, and some in Leicestershire, they violently cut and break down hedges, filled up ditches, and laid open all such enclosures of commons or other grounds as they found enclosed, which of ancient time had been open and employed to tillage, these tumultuous persons in Northamptonshire, Warwick and Leicestershire grew very strong, being in some places of men, women and children a thousand together, and at Hill Norton in Warwickshire there were three thousand, and at Cottesbich here assembled of men, women and children to the number of full five thousand. (3)

The real cost of the enclosures

The protesters said that it had been ‘credibly reported unto them by many that of late years there were three hundred and fifty towns decayed and depopulated, and that they supposed by this insurrection and casting down of enclosures to cause reformation.’ A gibbet was set up in the city of Leicester as a warning not to get involved. It was torn down by the people.

These riotous persons bent all their strength to level and lay open enclosures without exercising any manner of force or violence upon any man’s persons, goods or cattle, and wheresoever they came, they were generally relieved by the near inhabitants, who sent them not only carts laden with victual, but also good store of spades and shovels…

Mystery leaders

The rebels appeared to be well organised, but the leadership was at first a mystery:

At first these foresaid multitudes assembled themselves without any particular head or guide, then started up a base fellow named John Reynoldes, whom they surnamed Captain Pouch because of a great leather pouch which he wore by his side. He said there was sufficient matter to defend them against all comers, but afterwards when he was apprehended his pouch was searched, and therein was only a piece of green cheese.

The landowners, in particular the Treshams, raised an army and with the encouragement of the king suppressed the rebellion. Forty peasants were killed in a battle at the village of Newton in Northamptonshire. The rebels were indicted with High Treason and several were executed, including Captain Pouch, who was ‘made exemplary.’

At Newton, a contemporary account by the Earl of Shrewsbury reported that the protesters called themselves ‘levellers’. Others described themselves as ‘diggers’. The diggers of Warwickshire issued a proclamation to all other diggers:

Wee, as members of the whole, doe feele the smarte of these incroaching Tirants, which would grind our flesh upon the whetstone of poverty, and make our loyall hearts to faint with breathing, so that they may dwell by themselves in the midst of theyr heards of fatt weathers [herds of fat wethers].(4)

The Levellers: setting all things straight

These first levellers and diggers were easily suppressed, but not for good, and forty years later the terms re-emerged with increased vigour. In October 1647, in the celebrated Putney debates, Colonel Thomas Rainsborough stood before the assembled Grandees of Parliament, and declared, ‘For I really think that the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live, as the greatest he.’ Rainsborough was the spokesman at Putney for the Levellers, a political movement  that derived support from soldiers in several regiments of Cromwell’s New Model Army, and radical tradesmen in the City of London. The intention of the Levellers was to ‘set all things straight, and to raise a party and community in the kingdom.’

that derived support from soldiers in several regiments of Cromwell’s New Model Army, and radical tradesmen in the City of London. The intention of the Levellers was to ‘set all things straight, and to raise a party and community in the kingdom.’

No to royalty and gentry

General Ireton for the Grandees replied to Rainsborough. Only those with a ‘permanent fixed interest [ie owning land] in this kingdom,’ he argued, should have a part in disposing of the kingdom’s affairs. But the Levellers were determined that the English revolution should not overthrow a tyranny of kings only to see it replaced by a tyranny of landed gentry. A year earlier Richard Overton had pleaded, ‘let not the greatest peers in the land be more respected with you than so many old bellows-winders, broommen, cobblers, tinkers, or chimneysweepers, who are all equally freeborn.’ (5) Overton called for enclosed lands to be returned to the people:

That all grounds which anciently lay in Common for the poor, and are now impropriate, inclosed and fenced in, may forthwith (in whose hands soever they are) be cast out, and laid open again to the free and common use and benefit of the poor. (6)

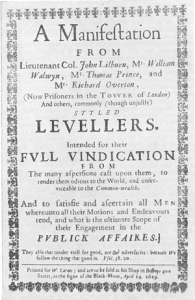

Leveller manifesto

In the main Leveller manifesto, the principle demands were for an extension of voting rights to everyone over 21 (except that is for beggars, servants, Royalists, and women), annual Parliaments with an elected representative for every 400 people, the application of laws equally to all people, and freedom of religious conscience.

They also proposed that all taxes should be abolished, saving only a tax on land: ‘an equal rate in the pound on every real and personal estate in the Nation.’ (7) However, in their manifesto, the Levellers were careful to dissociate themselves from more radical demands which they claimed would ‘level men’s Estates, destroy Property, or make all things Common.’ This was a reference to the programme of the ‘True Levellers’, known also as the ‘Diggers’.

Abiezer Coppe the ranter

The Ranters, as their enemies called them, also flourished during the English Civil War. They were social revolutionaries and mystics, convinced that the only divinity was to be found within the individual human being. They also believed that those in possession of such divinity were free spirits for whom absolutely nothing, however unconventional or shocking, could be sinful.

The most celebrated of all the Ranters was a renegade Anabaptist preacher named Abiezer Coppe (1619-1672). He identified himself with the most destitute, the most wretched, the most oppressed:

The most celebrated of all the Ranters was a renegade Anabaptist preacher named Abiezer Coppe (1619-1672). He identified himself with the most destitute, the most wretched, the most oppressed:

Mine eares are filled brim full with cryes of poore prisoners, Newgate, Ludgate cryes (of late) are seldome out on mine eares. Those dolefull cryes, Bread, bread, bread for the Lords sake, pierce mine eares, and heart, I can no longer forbeare. (8)

Extreme levelling

Coppe advocated an extreme form of levelling, where all property would be relinquished by the individual, and everything would be held in common.

Give, give, give, give up, give up your houses, horses, goods, gold, Lands, give up, account nothing your own, have ALL THINGS common, or els the plague of God will rot and consume all that you have.

He believed that the new millennium was imminent, in which property rights would be abolished, social equality would flourish, and the divinity inherent in mankind would find full expression:

It’s but yet a little while, and the strongest, yea, the seemingly purest propriety [property], which may mostly plead priviledge and Prerogative from Scripture, and carnall reason; shall be confounded and plagued into community and universality. And ther’s a most glorious design in it: and equality, community, and universall love; shall be in request to the utter confounding of abominable pride, murther, hypocrisie, tyranny and oppression.( 9)

Spiritual rebirth

Coppe rejected both ‘sword-levelling’ and ‘digging-levelling’ in favour of an ecstatic spiritual rebirth which would be achieved by direct and intense social interaction with the common people. So he made a point of swearing, kissing beggars in the streets, consorting with gypsies, living promiscuously, and confounding ‘plaguy holiness and righteousness’ by ‘skipping, leaping, dancing, like one of the fools.’ For Coppe the man of sin was a ‘brisk, spruce, neat, self-seeking, fine finiking fellow.’

Communitarian principles

Coppe rejected the pomp and ritual of all organised religion in favour of a life based on the most simple and direct communitarian principles: ‘The true breaking of bread – is from house to house, &c. Neighbours [in singleness of heart] saying if I have any bread, &c. it’s thine, I will not call it mine own, it’s common. These are true Communicants, and this is the true breaking of bread among men.’ (10)

Coppe rejected the pomp and ritual of all organised religion in favour of a life based on the most simple and direct communitarian principles: ‘The true breaking of bread – is from house to house, &c. Neighbours [in singleness of heart] saying if I have any bread, &c. it’s thine, I will not call it mine own, it’s common. These are true Communicants, and this is the true breaking of bread among men.’ (10)

This was dangerous stuff, condemned on all sides. Coppe was imprisoned and twice forced to publish recantations (although contemporary accounts doubted their sincerity). He died in 1672, of illnesses produced by ‘drinking and whoring’, as his enemies reported.

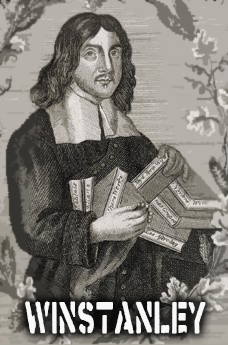

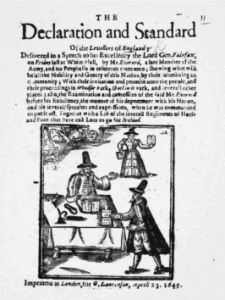

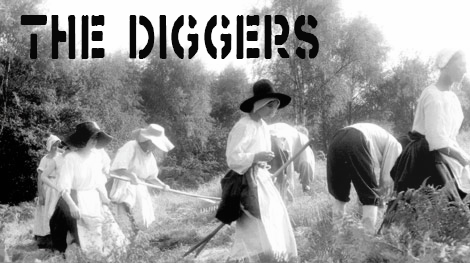

Gerrard Winstanley and the Diggers

On April Fool’s day in 1649 half a dozen men began to dig common land at St George’s Hill, Weybridge, in Surrey. Their leader, Gerrard Winstanley, was a bankrupt cloth merchant turned cattle herdsman, who claimed he had received a divine injunction that people should ‘work together; eat bread together’.

True Levellers?

The numbers tripled within a week. They called themselves True Levellers and soon became known simply as the Diggers. They were arrested and locked in a church, released and locked up again. An angry neighbour said, ‘They invite all to come and help them, and promise them meat, drink and clothes. They do threaten to pull down and level all park pales, and lay open, and intend to plant there very shortly… It is feared they have some design in hand.’ They certainly did, and within weeks Winstanley published a pamphlet to explain his ‘design’:

The earth (which was made to be a Common Treasury of relief for all, both Beasts and Men) was hedged in to In-closures by the teachers and rulers, and the others were made Servants and Slaves: And that Earth that is within this Creation made a Common Store-house for all, is bought and sold, and kept in the hands of a few, whereby the great Creator is mightily dishonoured, as if he were a respector of persons, delighting in the comfortable Livelihoods of some, and rejoycing in the miserable povertie and straits of others. From the beginning it was not so. (11)

St Georges Hill community

The plan at St George’s Hill was to ‘lay the Foundation of making the Earth a Common Treasury for All, both Rich and Poor… Not Inclosing any part into any particular hand, but all as one man, working together, and feeding together as Sons of one Father, members of one Family; not one Lording over another, but all looking upon each other, as equals in the Creation.’ St George’s Hill was to be only the beginning: Winstanley envisaged a vast series of collective communities: ‘not only this Common, or Heath should be taken in and Manured by the People, but all the Commons and waste Ground in England, and in the whole World, shall be taken in by the People.’

Common Community

Once in possession of their birthright, the people will never let it go: ‘wheresoever there is a People, thus united by Common Community of livelihood into Oneness, it will become the strongest Land in the World, for then they will be as one man to defend their Inheritance.’ War and division would cease: ‘Propriety [property] and single Interest, divides the People of a land, and the whole world into Parties, and is the cause of all Wars and Bloudshed, and Contention every where.’

Winstanley and his follower William Everard were summoned to Whitehall to be questioned by Lord Fairfax, the army chief. They stood before Fairfax with their hats on, and when asked why they did this, they replied, ‘Because he was but their fellow creature.’ They proclaimed, ‘what they did was to restore the ancient community of enjoying the fruits of the earth, and to distribute the benefits thereof to the poor and needy, and to feed the hungry and to clothe the naked.’

Winstanley and his follower William Everard were summoned to Whitehall to be questioned by Lord Fairfax, the army chief. They stood before Fairfax with their hats on, and when asked why they did this, they replied, ‘Because he was but their fellow creature.’ They proclaimed, ‘what they did was to restore the ancient community of enjoying the fruits of the earth, and to distribute the benefits thereof to the poor and needy, and to feed the hungry and to clothe the naked.’

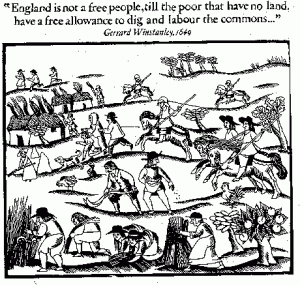

Attacked

Back on St George’s Hill, when the Diggers tried to cut and sell wood on the common land, their horses were attacked by local landowners. Then ‘divers men in women’s apparele on foot, with every one a staffe or club’ attacked the Diggers. When this failed to dislodge them, the landlords took to the courts. Bailiffs confiscated the cows, but wellwishers recovered them. Winstanley then moved the community to Cobham Manor, built four houses and prepared the land for a crop of winter grain. But troops were sent in October and November and on the second occasion they pulled down the houses. The Diggers built themselves ‘some few little hutches like calf-cribs’, and slept there at night, continuing to plant wheat and rye, ‘counting it a great happiness to be persecuted for righteousnesse sake, by the Priests and Professors.’

They denied slanders that they were thieves or that they held women in common: ‘I own this to be a truth, That the earth ought to be a common Treasury to all; but as for women, Let every man have his own wife, and every woman her own husband,’ said Winstanley. They survived the winter and by April 1650 had sown eleven acres of corn and had built seven houses. The vicar of Horsley sent a group of men to demolish one of the houses, ill-treating the occupier’s pregnant wife, who suffered a miscarriage.

Diggers resist

Winstanley tried to negotiate a settlement, promising that the Diggers would not cut wood on the common if the neighbours would not pull down their houses. But on Easter Friday they were attacked by fifty men, who burnt down the houses and scattered their belongings across the common. In frustration Winstanley wrote that if the Diggers beg ‘they whip them by their Law for vagrants, if they steal they hang them; and if they set themselves to plant the Common for a livelihood, that they may neither beg nor steale, and whereby England is inriched, yet they will not suffer them to do this neither.’ The settlement was destroyed but Winstanley remained defiant. ‘And now they cry out the Diggers are routed, and they rang bells for joy; but stay Gentlemen, your selves are routed, and you have lost your Crown, and the poor Diggers have won the Crown of glory.’

Winstanley tried to negotiate a settlement, promising that the Diggers would not cut wood on the common if the neighbours would not pull down their houses. But on Easter Friday they were attacked by fifty men, who burnt down the houses and scattered their belongings across the common. In frustration Winstanley wrote that if the Diggers beg ‘they whip them by their Law for vagrants, if they steal they hang them; and if they set themselves to plant the Common for a livelihood, that they may neither beg nor steale, and whereby England is inriched, yet they will not suffer them to do this neither.’ The settlement was destroyed but Winstanley remained defiant. ‘And now they cry out the Diggers are routed, and they rang bells for joy; but stay Gentlemen, your selves are routed, and you have lost your Crown, and the poor Diggers have won the Crown of glory.’

Digger colonies

Meantime at Wellingborough in Northampton, where over a thousand inhabitants were receiving alms and public relief, nine men led by Richard Smith began ‘to bestow their righteous labour upon the common land at Bareshanke.’ They resolved not to dig up any man’s property ‘until they freely give it us’ and they were pleased to discover that ‘there were not wanting those that did.’ Other Digger colonies were established at Wellingborough in Northamptonshire, Cox Hall in Kent, Iver in Buckinghamshire, Barnet in Hertfordshire, Enfield in Middlesex, Dunstable in Bedfordshire, Bosworth in Leicestershire, and at other sites in Gloucestershire and Nottinghamshire.

Beyond commoner rights

In 1649 Winstanley claimed that ‘Reason requires that every man should live upon the increase of the earth comfortably,’ asserting that half or two thirds of the land of England was not properly cultivated: ‘If the waste land of England were manured by her children, it would become in a few years the richest, the strongest and [most] flourishing land in the world.’ (12) This went beyond an attempt to defend traditional commoner rights against those who argued, perhaps correctly, that more intensive farming methods were needed to supply the needs of the growing population. Winstanley argued that collective cultivation of the land by the poor, as an alternative to expropriation by the rich, could generate both prosperity and social justice.

The Law of Freedom in a Platform

His plan for social reformation was set out in 1652 in his greatest work: The Law of Freedom in a Platform.(13) Here he states his quest: ‘The great searching of heart in these days is to find out where true freedom lies, that the commonwealth of England might be established in peace.’ The solution lies in the restoration of common land to the community as a whole: ‘True freedom lies in the free enjoyment of the earth.’ Winstanley proposed that all land confiscated from royalists and from the dissolution of the monasteries a century earlier should be added to a commonwealth land fund. Private ownership of land or the produce of the land would be abolished (although families would retain ownership of their houses and property within it), money would disappear, and communal storehouses would be set up:

His plan for social reformation was set out in 1652 in his greatest work: The Law of Freedom in a Platform.(13) Here he states his quest: ‘The great searching of heart in these days is to find out where true freedom lies, that the commonwealth of England might be established in peace.’ The solution lies in the restoration of common land to the community as a whole: ‘True freedom lies in the free enjoyment of the earth.’ Winstanley proposed that all land confiscated from royalists and from the dissolution of the monasteries a century earlier should be added to a commonwealth land fund. Private ownership of land or the produce of the land would be abolished (although families would retain ownership of their houses and property within it), money would disappear, and communal storehouses would be set up:

Every tradesman shall fetch materials, as leather, wool, flax, corn and the like, from the public store-houses, to work upon without buying and selling; and when particular works are made, as cloth, shoes, hats and the like, the tradesmen shall bring these particular works to particular shops, as it is now in practice, without buying and selling. And every family as they want such things as they cannot make, they shall go to these shops and fetch without money.

Commerce, he believed, would thrive under such arrangements:

Every man shall be brought up in trades and labours, and all trades shall be maintained with more improvement, to the enriching of the commonwealth.

Elected Councils

Elected councils would govern at local levels, and these would send elected representatives to national government. As in Thomas More’s Utopia, there would be no lawyers. Education would be universal and enable men and women to discover the ‘secrets of Nature and Creation within which all true knowledge is wrapped up.’ No one would work beyond the age of forty.

Winstanley recognized that it was no easy thing for people to live together harmoniously in a community. He accepted that in any parish ‘the body of the people are confused and disordered, because some are wise, some foolish, some subtle and cunning to deceive, others plain-hearted, some strong, some weak, some rash, angry, some mild and quiet-spirited.’ Therefore ‘peacemakers’ would be annually elected in every parish ‘to prevent troubles and to preserve common peace.’

Societal organisation

Similarly, elected ‘overseers’ would maintain order and ensure effective production and exchange: ‘they are to see that particular tradesmen, as weavers of linen and woollen cloth, spinners, smiths, hatters, glovers and such like, do bring in their works into the shops appointed; and they are to see that the shops and storehouses within their several circuits be kept still furnished: [and] that when families of other trades want such commodities as they cannot make, they may go to the shops and storehouses where such commodities are, and receive them for their use without buying or selling.’

The third type of elected officer in every parish would be the ‘postmasters’. These would keep monthly records of events and transactions within the parish, and share these records with other parishes and with the nation as a whole. This would allow all communities to assist each other in the case of disaster, avoid mistakes that others had made, and share discoveries and innovations:

The benefit lies here, that if any part of the land be visited with plague, famine, invasion or insurrection, or any casualties, the other parts of the land may have speedy knowledge, and send relief.

And if any accident fall out through unreasonable action or careless neglect, other parts of the land may thereby be made watchful to prevent like danger.

Or if any through industry or ripeness of understanding have found out any secret in nature, or new invention in any art or trade or in the tillage of the earth, or such like, whereby the commonwealth may more flourish in peace and plenty, for which virtues those persons received honour in the places where they dwelt:

When other parts of the land hear of it, many thereby will be encouraged to employ their reason and industry to do the like, that so in time there will not be any secret in nature which now lies hid (by reason of the iron age of kingly oppressing government) but by some or other will be brought to light, to the beauty of our commonwealth.

Proposals dismissed

Winstanley’s proposals were dismissed, and the Diggers were rapidly and ruthlessly suppressed by the aspiring landowners within Cromwell’s Protectorate. The restoration of Charles II was followed by the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 in which, though the monarchy’s powers were limited, the landowning classes took political and economic control. Exactly what the Levellers and Diggers had most feared had come to pass, and the ‘common treasury’ was once again denied to the people.

Relevance for a permanent culture now

Movements can reappear

The case of the Levellers, Ranters and Diggers show that movements and ideas that appear to be crushed can reemerge years on, you could argue that Occupy is the latest incarnation of these ideas of equality and justice. This points to the need to keep these ideas present and in societies consciousness even when it appears that they have had their time. As long as the fundamental dynamics of inequality and power exist, I believe that these ideas and movements will reemerge in different forms and organisation until they are resolved.

Direct Action

Captain Pouch and the Diggers undertook what is now called direct action. They attacked directly the things that oppressed them in the way that climate change protestors occupy power stations and GM activists destroy crops. Captain Pouch and his followers took it onto themselves to destroy the enclosures that were destroying their lives. The Diggers attempted to create the Utopia they sought through creating the communtities and putting their ideas into practice to meet their needs, modern day equivalents are many from the Peace Convoy and New Age Traveller movements of the 1980’s and 90’s to the intentional communities and communes of the 196’s to the housing coops and Eco villages of today. They all follow in the footsteps of the Diggers.

Manifestos

All the movements mentioned in this series had strong ideas about the way society should be organised and they were often printed in manifestos in order to spreads their ideas widely. The Diggers manifesto predates Marx’s Communist Manifesto by hundreds of years, yet it can be seen as pre-cursor to Marx’s idea of communism. The use of manifestos are still very much with us today with as different economic models being proposed, green manifestos highlighting the need to save the planet to the commons movement that is once again arguing for resources to be held in common as Winstanley and the Diggers did in the past.

Diggers songs

Two versions of the World turned upside down song about the diggers the first by Leon Rosselson who wrote the song the second a cover by Billy Bragg.

Talk about the diggers by Gerard Winstanleys distant relative:

More Information:

Site about Capitan Pouch and the Newton Rebels

English Civil War Site with section about the Levellers

Excerpt of Abiezer Coppes Writings

Radical religion in the Civil War

Selection of Levellers writings

References:

3. John Stow and E Howes, Annales of England, London 1632, p 890.

4. Also see www.newtonrebels.org.uk.

5. Richard Overton, An Arrow Against all Tyrants, 1646.

6. ‘Certain Articles for the Good of the Commonwealth’ in Appeale from the Degenerate Representative Body, 1647.

7. John Lilburne, William Walwyn, Thomas Prince, Richard Overton, An Agreement of the Free People of England, 1649.

8. Abiezer Coppe, A Fiery Flying Roll, 1649, I, 2.3 in Abiezer Coppe, Selected Writings, ed. Andrew Hopton, 1987.

9. Abiezer Coppe, A Fiery Flying Roll, 1 649, II, 2.6; 6.2.

10. Abiezer Coppe, A Fiery Flying Roll, 1649, II, 5.5; 7.1; 8.9.

11. Gerrard Winstanley, The True Levellers Standard Advanced, or The State of Community Opened, and Presented to the Sons of Men, April 20 1649.

12. Gerrard Winstanley, The New Law of Righteousness, 1649.

13. Gerrard Winstanley, The Law of Freedom in a Platform, 1652.

What incredible courage the Levellers had – and how hard they must have been pressed. The trouble with advanced capitalism in this country is that it bribes us so effectively.