This is an on-going serialisation we are doing of a great little book called, ‘A history of community asset ownership’ by Steve Wyler who has kindly agreed for us to reprint his book on our website. We think a much better title for the book would be ‘The UK common peoples history’. We at Permanent Culture Now were going to do a very similar take on History that Steve has done with his book, so when we saw it we were like that’s great someone has already done the hard work. So we are expanding the work by adding our views as to why this history is relevant for today, drawing parallels with then and now and taking from it inspiration for building a more permanent culture.

A common peoples history of the UK part 4: The people’s farm

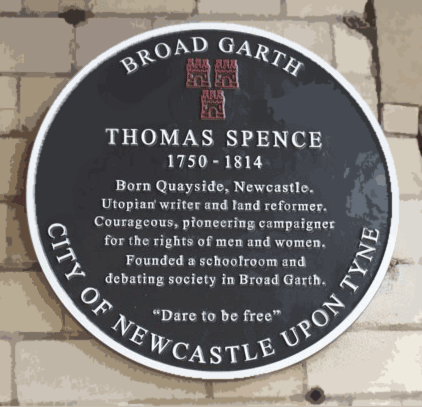

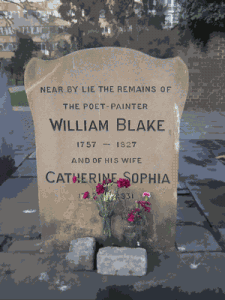

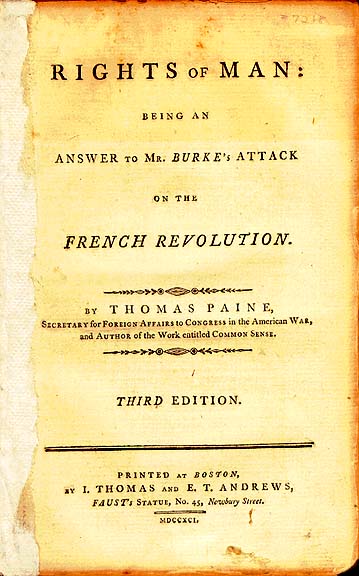

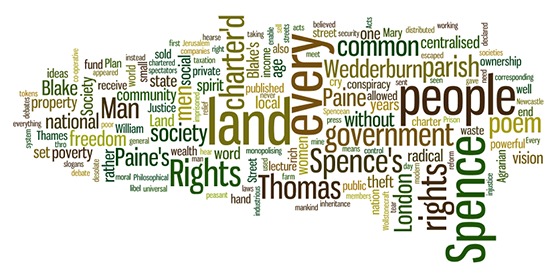

In 1775 the schoolmaster Thomas Spence gave a lecture to the Newcastle Philosophical Society which set out a vision of a new millennium, where poverty would be at an end and social justice would reign, founded on community ownership of land and community self-government. Spence’s ideas contributed to the ferment of radicalism that flourished in the years following the French Revolution. In 1791 appeared Tom Paine’s Rights of Man followed by Mary Wollstonecraft’s Rights of Men, and a few years later by Paine’s Agrarian Justice. William Blake’s poem ‘London’ expressed the social desolation of a ‘charter’d’ urban landscape.

In 1775 the schoolmaster Thomas Spence gave a lecture to the Newcastle Philosophical Society which set out a vision of a new millennium, where poverty would be at an end and social justice would reign, founded on community ownership of land and community self-government. Spence’s ideas contributed to the ferment of radicalism that flourished in the years following the French Revolution. In 1791 appeared Tom Paine’s Rights of Man followed by Mary Wollstonecraft’s Rights of Men, and a few years later by Paine’s Agrarian Justice. William Blake’s poem ‘London’ expressed the social desolation of a ‘charter’d’ urban landscape.

Thomas Spence

In 1775 Thomas Spence, an impoverished schoolmaster, delivered and published a lecture to the Newcastle Philosophical Society. ‘The Real Rights of Man’, was the title of his lecture, and Spence’s thesis was that poverty and injustice in an age of rapidly increasing material prosperity were the direct consequence of theft from the people of land, their common inheritance. Spence’s ‘Plan’ would restore this inheritance.

Reclaim the land for the people

A day would be appointed on which all land would be reclaimed by the people, and pass into ownership and control of parish corporations. Land would then be leased out to the highest bidders, and rental income would replace all other taxation. Every parish would be self governing, and would set its own laws, and every adult (women as well as men) with residence of a year would enjoy full citizenship rights.

Money raised locally by land taxation could provide for relief of the poor, universal education, roads, canals, hospitals, schools, ‘planting and taking in waste ground’, and training local citizens in the use of arms. A small proportion of the tax would be sent to national government (representatives would be elected annually by every parish). Government would not interfere in local laws and decisions, except where these threatened the ‘rights and liberties of mankind’.

Money raised locally by land taxation could provide for relief of the poor, universal education, roads, canals, hospitals, schools, ‘planting and taking in waste ground’, and training local citizens in the use of arms. A small proportion of the tax would be sent to national government (representatives would be elected annually by every parish). Government would not interfere in local laws and decisions, except where these threatened the ‘rights and liberties of mankind’.

Meet the needs of society

There would be sufficient income for all the needs of society, because there would be no need for an expensive centralised officialdom: in Spence’s scheme ‘the government, which may be said to be the greatest mouth, having neither excisemen, custom-house men, collectors, army, pensioners, bribery, nor such like ruination vermin to maintain, is soon satisfied.’ If someone were to arrive in need from a foreign land, they should be provided with relief by the parish, but the cost should be defrayed from the parish contribution to the national exchequer. Thus, refugees would be helped, but not looked upon with ‘an envious eye.’ Any funds left over would be distributed as equal dividends to all members of the population, the elderly and infants included. Free trade and manufacture, a flourishing agriculture, and localised democracy would combine to raise the nation to a high moral level, a people’s Jubilee.

Emancipation of women

Spence spoke out for the emancipation of women as well as men: he declared that women not only knew their rights ‘but have spirit to assert them.’ He even proposed that in every parish a committee of women (rather than their ‘gallant lock-jawed spouses and paramours’) would manage the business of collecting rental income and commissioning public works. The ‘end of society is common happiness’, declared the first article of Spence’s proposed Constitution. He believed in minimal government, and that people should be allowed to live freely, provided only that they do not restrict the rights of other people: ‘liberty is that power which belongs to a man which does not hurt the rights of another.'(14)

Keep your wealth, but not the wealth

Spence was not hostile to personal wealth. He told the wealthy that they would be allowed to keep ‘all your moveable riches and wealth, all your gold and silver, your rich clothes and furniture, your corn and cattle, and everything that does not appertain to the land as a fixture’.(15) He believed that commerce would thrive under his system: ‘the uncommon freedom, and security of property in such a happy state would operate as a stimulus rather than a check to industry.’ A multitude of small tradesmen would replace monopolising corporations, for ‘great, avaricious monopolising companies… for their private ends, disturb the peace of the whole world, setting nation against nation, and people against people.'(16)

Chancery Lane

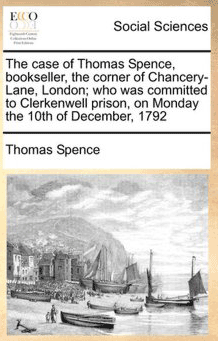

In 1792 Spence travelled to London and set up a street stall on Chancery Lane. He sold a rum punch, distributed radical propaganda. He also produced trade tokens, with slogans and images to spread his messages. On one, a bonfire of land deeds signals the end of oppression. Sometimes Spence would sell his tokens, sometimes he would scatter them into the London crowd.

Frequently imprisoned

Frequently imprisoned, Thomas Spence never gave up, and attracted a group of dedicated followers – small groups of working men, including the Black radical Robert Wedderburn, the son of a Jamaican slave. The Spenceans met in pubs, chalked slogans on the walls: ‘Spence’s Plan and Full Bellies’, ‘The Land is the People’s Farm’. In 1801 they inspired bread riots.

Frequently imprisoned, Thomas Spence never gave up, and attracted a group of dedicated followers – small groups of working men, including the Black radical Robert Wedderburn, the son of a Jamaican slave. The Spenceans met in pubs, chalked slogans on the walls: ‘Spence’s Plan and Full Bellies’, ‘The Land is the People’s Farm’. In 1801 they inspired bread riots.

Spence dies

Spence died in 1814 and was buried by forty followers, and a Society of Spencean Philanthropists led by Wedderburn was formed. Wedderburn opened a Unitarian chapel in Hopkins Street, Soho and government spies reported that he was making ‘violent, seditious, and bitterly anti-Christian Spencean speeches’. In 1817, Robert Wedderburn wrote ‘The earth cannot be justly the private property of individuals, because it was never manufactured by man; therefore whoever sold it, sold that which was not his own.'(17) By 1819 up to 200 people were paying 6d. a head to attend debates, and ‘lectures every Sabbath day on Theology, Morality, Natural Philosophy and Politics by a self-taught West Indian’. Frustrated in their attempts to promote Spence’s Plan through rational argument, the Society turned to armed insurrection. In 1820 after the fiasco of the Cato Street conspiracy (a bungled attempt to assassinate members of the government), its leaders were executed or transported.

Wedderburn oppose the conspiracy

Wedderburn himself opposed the conspiracy, but only because he thought it was premature. Eventually he was charged with blasphemous libel. In court he asked the jury: ‘Where, after all, is my crime? It consists merely in having spoken in the same plain and homely language which Christ and his disciples uniformly used. There seems to be a conspiracy against the poor, to keep them in ignorance and superstition’. Found guilty he was sentenced to two years in Dorchester Prison. On his release Wedderburn continued to campaign for press freedom, against injustice, and for the ideas of Thomas Spence. In 1824 he published The Horrors of Slavery. In 1831, at the age of 68, he was arrested once more and sent to Giltspur Street Prison; four years later he died.

Mary Wollstonecraft and Thomas Paine

Spence’s ideas found echoes among other radical writers of his generation. In 1790 Mary Wollstonecraft published A Vindication of the Rights of Men where she sketched a vision of society without extremes of wealth and poverty, where property is divided more equitably, and independent smallholders form the basis of the economy. She suggested that the ‘industrious’ peasant should be permitted to take over and cultivate unused land:

Spence’s ideas found echoes among other radical writers of his generation. In 1790 Mary Wollstonecraft published A Vindication of the Rights of Men where she sketched a vision of society without extremes of wealth and poverty, where property is divided more equitably, and independent smallholders form the basis of the economy. She suggested that the ‘industrious’ peasant should be permitted to take over and cultivate unused land:

Why does the brown waste meet the traveller’s view, when men want work? But commons cannot be enclosed without acts of parliament to increase the property of the rich! Why might not the industrious peasant be allowed to steal a farm from the heath?

The Rights of Man

In 1791 and 1792 appeared Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man, in two parts. He pointed out that society can operate perfectly well without a centralised government of the few over the many:

In 1791 and 1792 appeared Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man, in two parts. He pointed out that society can operate perfectly well without a centralised government of the few over the many:

The instant formal government is abolished, society begins to act: a general association takes place, and common interest produces common security. How often is the natural propensity to society disturbed or destroyed by the operations of government! When the latter, instead of being ingrafted on the principles of the former, assumes to exist for itself, and acts by partialities of favour and oppression, it becomes the cause of the mischiefs it ought to prevent.

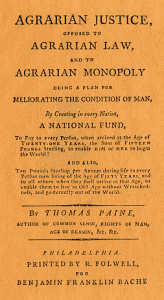

The Rights of Man was a bestseller, bought in installments in cheap editions by working class radicals through ‘corresponding societies’. Soon both The Rights of Man and the corresponding societies were outlawed, and Paine was charged with seditious libel. Paine escaped and fled to France where he became a member of the Convention, but, falling into disfavour with the increasingly despotic revolutionaries, Paine was imprisoned and only narrowly escaped the guillotine. He made his way to the United States and, in 1797, wrote the most famous pamphlet of land reform: Agrarian Justice.

Agarian Justice

Paine’s proposals were that all landowners should pay ‘to the community a groundrent’ to be accumulated in a national fund. From this fund every person reaching the age of twenty one would receive a bounty of ‘Fifteen Pounds Sterling to enable him, or her, to begin in the World.’ He also called for a universal old age pension: all persons aged fifty or above would receive an annuity of £10 ‘to enable them to live in Old Age without Wretchedness, and go decently out of the world.’

Paine’s proposals were that all landowners should pay ‘to the community a groundrent’ to be accumulated in a national fund. From this fund every person reaching the age of twenty one would receive a bounty of ‘Fifteen Pounds Sterling to enable him, or her, to begin in the World.’ He also called for a universal old age pension: all persons aged fifty or above would receive an annuity of £10 ‘to enable them to live in Old Age without Wretchedness, and go decently out of the world.’

The state would provide

However, Paine’s proposals did not allow for local community ownership or control. The state, through the national fund, would provide for all. Thomas Spence saw the danger in this: in 1797 he accused Paine of promoting ‘the sneaking unmanly spirit of conscious dependence’:

Under the system of Agrarian Justice, the people will, as it were, sell their birthright for a mess of porridge, by accepting of a paltry consideration in lieu of their rights…

The people will become supine and careless in respect of public affairs, knowing the utmost they can receive of the public money. (18)

Above all Spence rejected Paine’s confidence in a centralised state: ‘instead of debating about mending the State’ it would be better, claimed Spence, to ’employ our ingenuity nearer home’:

The results of our debates [would appear] in every parish: how we shall work such a mine, make such a river navigable, or improve such a waste. These things we are all immediately interested in and have each a vote in executing; and thus we are not mere spectators in the world, but as men ought to be, actors. (19)

Beginning of state verses community debate

This was the beginning of a debate which was to run through the chartist, socialist and co-operative movements. Would social reform be best accomplished through a national Parliament and a centralised state, or by means of largely autonomous local communities? Should all people play an active and determining role, as actors rather than spectators, or should authority and resources be controlled through a highly educated and professionalised elite? The debate remains as relevant and unresolved today as it was in the 1790s

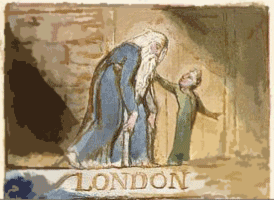

William Blake’s ‘Charter’d’ London

In the poem ‘London’, which William Blake printed by hand in 1794 as one of his Songs of Experience, (20) the causes of poverty and the nature of the modern Babylon are identified: the theft of common land from the people, and the consequent debasement of social value by means of squalid commercialism:

In the poem ‘London’, which William Blake printed by hand in 1794 as one of his Songs of Experience, (20) the causes of poverty and the nature of the modern Babylon are identified: the theft of common land from the people, and the consequent debasement of social value by means of squalid commercialism:

I wander thro’ each charter’d street, Near where the charter’d Thames does flow And mark in every face I meet Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

First draft

The first draft of this poem has survived in Blake’s notebook, and from this we know that originally Blake used the phrase ‘dirty street’. The substitution ‘charter’d’ changes everything. The historian E. P Thompson remarks that ‘the word is standing at an intellectual and political cross-roads’, producing not a single meaning but a series of associations. (21) For contemporary readers the word ‘charter’d’ might have invoked the mighty chartered companies such as the East India Company, whose ships set out from the Thames, and whose operations were at the time under attack in the radical press. The word also alluded to the Whig concept of freedom (chartered liberty, the Magna Carta), but for Blake this was no true freedom claimed as of right, but rather a debased freedom handed out by the powerful. As Paine had written in The Rights of Man:

It is a perversion of terms to say that a charter gives rights. It operates by a contrary effect-that of taking rights away. Rights are inherently in all the inhabitants; but charters, by annulling those rights in the majority, leave the right, by exclusion, in the hands of a few…

Legalised theft of land

Above all the word ‘charter’d’ invokes the legalised theft of land from the people, by charter and Act of Parliament. In Blake’s lifetime the enclosure of common land was continuing at an unprecedented pace: during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries more than seven million acres of land were enclosed by a series of 4,200 private Acts and various general enclosure Acts. (22) The land (the ‘charter’d streets’) and even the rivers (the ‘charter’d Thames’) was once the birthright of the people, but had been expropriated by the rich and powerful. Blake explicitly linked the theft of land by charter to the distress of modern civilization, and the poem continues:

Above all the word ‘charter’d’ invokes the legalised theft of land from the people, by charter and Act of Parliament. In Blake’s lifetime the enclosure of common land was continuing at an unprecedented pace: during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries more than seven million acres of land were enclosed by a series of 4,200 private Acts and various general enclosure Acts. (22) The land (the ‘charter’d streets’) and even the rivers (the ‘charter’d Thames’) was once the birthright of the people, but had been expropriated by the rich and powerful. Blake explicitly linked the theft of land by charter to the distress of modern civilization, and the poem continues:

In every cry of every Man, In every Infants cry of fear, In every voice: in every ban, The mind-forg’d manacles I hear. How the Chimney-sweeper’s cry Every blackning Church appalls, And the hapless Soldiers sigh Runs in blood down Palace walls.

But most thro midnight streets I hear How the youthful Harlots curse Blasts the new-born Infants tear And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse.

Blake’s London

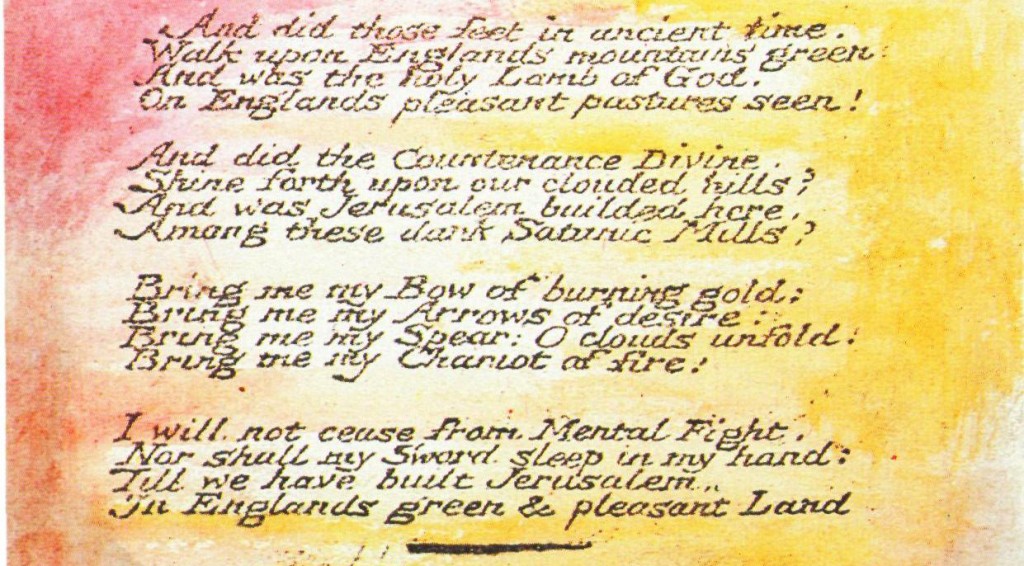

Thompson points out that ‘Blake’s “London” is not seen from without as spectacle. It is seen, or suffered, from within, by a Londoner.’ This is a poem whose ‘moral realism is so searching that it is raised to the intensity of apocalyptic vision.’ As the poem progresses the narrator takes the reader with him ever deeper into the sights and sounds of the desolate city. Commercial transactions and the institutions of the powerful destroy the human spirit, ultimately corrupting all that is created (‘the newborn infant’s tear’) and blighting all human attempts at unification (‘the Marriage hearse’).Later, Blake was to express the antithesis of this desolate vision as the reawakening and re-unification of ‘Albion’, the embodiment of England and of all mankind, and in his epic poem Jerusalem appears one of the finest articulations of the early co-operative or ‘socialist’ spirit:

Thompson points out that ‘Blake’s “London” is not seen from without as spectacle. It is seen, or suffered, from within, by a Londoner.’ This is a poem whose ‘moral realism is so searching that it is raised to the intensity of apocalyptic vision.’ As the poem progresses the narrator takes the reader with him ever deeper into the sights and sounds of the desolate city. Commercial transactions and the institutions of the powerful destroy the human spirit, ultimately corrupting all that is created (‘the newborn infant’s tear’) and blighting all human attempts at unification (‘the Marriage hearse’).Later, Blake was to express the antithesis of this desolate vision as the reawakening and re-unification of ‘Albion’, the embodiment of England and of all mankind, and in his epic poem Jerusalem appears one of the finest articulations of the early co-operative or ‘socialist’ spirit:

In my Exchanges every Land Shall walk, & mine in every Land, Mutual shall build Jerusalem: Both heart in heart & hand in hand. (23)

The writings of Thomas Spence, linked inequality to the theft of land from the common people, this is still an issue today in the western world as people struggle to provide shelter and food for themselves as they have very little access to land on any scale and all land is still owned by the ruling class who stole it under the auspices of enclosure acts. In other parts of the world people are routinely dispossessed of their land in the name of capitalist development, for example in China as rural communities are displaced and people then forced into cities, as well as the massive land grabs occurring in Africa and elsewhere as other countries buy up fertile land to feed their own populations.

Spence was also a champion of land being managed for the good of all people through localised decision making and did not see the point of centralised bureaucracies and saw the state as a bloated body that was not needed. He actually formulated plans on how to run things locally and this theme of localisation is currently very much being debated at the present, though nowadays there would be a need for structures that could run a complex society in order to address resource depletion and climate change. These structures would have to accountable accountable to the local organisations under a system of recall whereby those granted the responsibility were instantly recallable.

We also like the fact that Spence was down with the common people and ran a rum punch stall, where he distributed radical propaganda and produced al kinds of trade tokens with radical messages. He was also not afraid of being imprisoned as he was frequently banged up for his actions. Thomas Spence is surely a man we would have liked to have shared a rum punch with. It is also important that even though Spence was not successful in his demand his influence was long lasting and he inspired those who came after him such as Wedderburn. This is always worth noting as sometimes people feel that there work is futile, yet we don’t know the ripples of history that we put in place like a stone being thrown into a lake, by our own actions.

Spence and Wollenscroft also where some of the first people to talk about the emancipation of women and thus equality of all. They also began to talk about rights and can be seen as a precursor for the Human Rights Act. Spence also believed that women should be in powerful positions in his vision of society and proposed that every parish should have a committee managed by women to oversee the collection of rent and the commissioning of public works. Considering this was in the 1700’s this was a radical approach to women’s rights.

Wedderburn was not only a advocate of Spence’s ideas, he was also a slavery campaigner and wrote extensively on this issue and he was also one of the first people to send revolutionary papers called “A fatal blow to oppressions, being an address to the planters and Negroes of the island of Jamaica“ to the West Indies. He also made links between race and class within capitalism, when he made links to the suffering of slaves in the African Colonies and the British establishment. His analysis of global capitalism and its impact resonates today as we see communities of people displaced and made wage slaves for the purposes of global capital.

Thomas Paine furthered this ideas, and he was also adverse to centralised government as all good radicals are.

As he states”How often is the natural propensity to society disturbed or destroyed by the operations of government!”

These ideas can be seen as a precursor to the strand of anarchist and communist thought that came after and are still being developed to this day. He also sold his book The Rights of Man in instalments cheaply, so his ideas could get out to the radical working class, we like to think that Thomas Paine would have been a avid user of the internet if he was around today and we feel that we are continuing his tradition of free/cheap access to radical ideas.

These ideas can be seen as a precursor to the strand of anarchist and communist thought that came after and are still being developed to this day. He also sold his book The Rights of Man in instalments cheaply, so his ideas could get out to the radical working class, we like to think that Thomas Paine would have been a avid user of the internet if he was around today and we feel that we are continuing his tradition of free/cheap access to radical ideas.

Paine and Spence although having many ideas in common, disagreed about the function of the state. We would have to side with Spence on this argument as he opposed the centralised state as form of organisation that promotes dependence rather than empowerment. I think its fair to say that the state in most countries acts in the interests of the dominant class of the time and currently takes away from local communities and common people as the Occupy movement so simply illustrates in its slogan around the 99%. This debate of how best to take power continues to this day throughout political organisations the world over.

William Blake is great because he makes the connection between the rise in inequality and poverty, with the rise of commercial exploitation of the land for private gain. He also saw the legalised theft of land occurring before his eyes as he lived through the enclosures of the time, he was correct to link the theft of land to the distress of modern civilisation. It is fair to say that modern day capitalism began continues to this day to profit through its access to land, as without access to land there is no access to resources, places to build factories, places to grow food and so on. He also crucially began to describe the effects of this dynamic on the souls of people and I doubt he would have been surprised to see the levels of the depression we now have in the Western world. He defined the socialist spirit in his epic poem Jerusalem, which Danny Boyle utilised to great ironic ends in the 2012 Olympics opening ceremony.

Blake’s Poem Jerusalem

More Information:

Political works of Thomas Spence

Talk by Bristol Radical History Group on Thomas Spence

Robert Wedderburn: race, religion and revolution Article

Robert Wedderburn wikipedia profile

Mary Wollstonecraft wikipedia profile

Mary Wollstonecraft A Vindication of the Rights Of Women – Full Text

Mary Wollstonecraft influence on feminism and women’s issues

Karla Carter on Mary Wollstonecraft, Part One

Thomas Paine Wikipedia Profile

Thomas Paine National Historical Association

BBC profile of Thomas PaineThe Thomas Paine Library – Online Works

Bristol Radical History Group talks and articles on Thomas Paine

Common Sense Audiobook by Thomas Paine (February 4, 1776)

Mark Steel on Thomas Paine

William Blake wikipedia profile

Pictures and poems of William Blake

Bristol Radical History Group Article on the real meaning of Jerusalem

William Blake Singing For England Documentary

Poems of William Blake

William Blake: Poet, Artist, Eccentric Genius

References

14. Thomas Spence, The Constitution of a Perfect Commonwealth, 1798.

15. Thomas Spence, Rights of Infants, 1797.

16. Thomas Spence, The Restorer of Society to its Natural State, 1801.

17. Robert Wedderburn, The Axe Laid to the Root, 1817

18. Thomas Spence: Rights of Infants, 1797.

19. Thomas Spence, Description of Spensonia, 1795.

20. William Blake, London, in Songs of Experience, 1794.

21. E. P. Thompson, ‘London’ in Witness Against the Beast: William Blake and the Moral Law (1993).

22. Marion Shoard, This Land is Our Land: The Struggle for Britain’s Countryside, 1987.

23. William Blake, Jerusalem, c. 1815, plate 27.

Love it!