Popular Education is a new way of teaching which offers a much more participative and democratic way of learning. The following gives an overview of Popular Education, what it is, how to do it, loads of films and links to more information.

Popular education overview

“Tell me, and I forget. Show me, and I remember. Involve me, and I understand.”(Chinese proverb)

Education, and in particular popular education, is vital to respond to the ecological, social and climatic crises we face and to achieve meaningful radical social change. An education where we relearn co-operation and responsibility that is critically reflective but creatively looks forward – an education that is popular, of and from the people. There are many examples of groups that organise their own worlds without experts and professionals, challenge their enemies and build movements for change. What we outline here is what is known as popular, liberatory or radical education which aims at getting people to understand their world around them, so they can take back control collectively, understand their world, intervene in it, and transform it. This chapter looks at the importance of education in bringing about social change, and indeed how social movements for change have popular education at their core.

So what does popular education mean?

The word ‘popular’ can mean many things and has been mobilised by the right as well as the left. There is no single political project behind the methods of popular education. It has been used by all sorts of people including revolutionary guerillas, feminists, and adult educators; all with different aims. Development practitioners from organisations such as the World Bank, for example, increasingly use popular or participatory education to co-opt, manipulate and influence communities to secure particular versions of development. Yet it is important to promote and reclaim some of the more radical strands of popular education which are rooted in defiance (‘we are not going to take this anymore’), and struggle (‘we want to change things’), and geared towards change (‘how do we get out of this mess’), while promoting solidarity (‘your struggle is our struggle’).

The Popular Education Forum of Scotland (Crowther, Martin and Shaw 1999) defines popular as:

1. Rooted in the real interests and struggles of ordinary people.

2. Overtly political and critical of the status quo.

3. Committed to progressive social and political change.

4. A curriculum which comes out of the concrete experience and material interests of people in communities of resistance and struggle.

5. A pedagogy which is collective, primarily focused on group rather than individual learning and development.

6. Attempts to forge a direct link between education and social action.

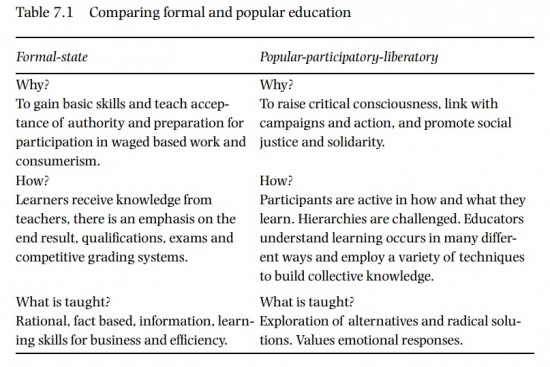

One of the activities that we have used in our workshops to start thinking about how we learn is to look at positive and negative learning experiences. People have told us that negative experiences are characterised by fear, discipline, constant assessment, humiliation, being bullied or bored, and unenthusiastic teachers. Positive experiences, on the other hand, are often those that are creative, interactive, student led, interesting, when learners are given responsibility, and take place in a supportive and friendly environment. Although many teachers in the state sector use participatory and progressive teaching methods, state funded education remains constrained by large class sizes, national curricula and targets. Table 7.1 outlines briefly some of the main differences between the overarching aims of formalised education in schools and universities, and popular education.

Key aspects of popular education

1. A commitment to transformation and solidarity

Popular educators are not experts who sit on the sidelines; they participate in social movements, be they literacy campaigns, teach-ins about globalisation or by participating in actions. Solidarity means being on the side of the marginalised and working with agendas and goals chosen by those affected, not outside agencies. Charity and aid can provide temporary relief but are rarely designed to break the chains of dependency and encourage people to run their own affairs. At the heart of popular education is a desire not just to understand the world, but to empower people so they can change it. By identifying and exposing power relations, we can begin to develop an understanding of how we might challenge ways of organising social and economic life which perpetuate injustice, at whatever scale. This type of education is not about explaining external problems, but also confronting each other and the social roles we have adopted. To make ‘other possible worlds’, we must also change ourselves and learn to listen to the experiences of others. It’s not enough to understand how we think power works ‘out there’ if we overlook our role in reproducing power. Asking questions rather than providing answers is fundamental: What do we accept and reject? How do we pass on systems of domination be they class, gender, ethnicity or sexuality? How can we challenge these within ourselves? This way of teaching and learning is challenging and requires effort on both sides. Paulo Freire called it the ‘practice of freedom’ and talked of the dialectical relationship between the oppressor and the oppressed. This is what Freire meant by conscientization, through which we recognise our presence in the world, and, rather than adapting or adhering to social norms, we realise our potential to intervene and challenge inequality.

2. Learning our own histories not his-story

Although there is always at least two sides to every story, the vast majority of official history is exactly that – ‘his-story’, written by the literate educated few, mainly men, not by peasants, workers or women. We are taught about leaders of world wars and histories of great scientists, but not much about the silent millions who struggle daily for justice. These are the ordinary people doing extraordinary things who are the invisible makers of history. When they do appear, they are often portrayed as violent extremists. Few learn about the Haymarket martyrs in nineteenth-century Chicago who fought for an eight hour day, the nineteenth-century Luddites who challenged the factory system during the Industrial Revolution, or the women who occupied the Shell platforms in Ogoniland, Nigeria. Many of these stories are not told because people could not read or write, or did not have any means to record events and communicate with a wider audience. They are not recorded by historians because they evoke the dangerous idea that ordinary people can act collectively and do it themselves. Talking about a proposed gas pipeline in County Mayo, Ireland, a campaigner reflected,

“A generation ago we could not have resisted this pipeline, because we could not read and write – we wouldn’t have been able to respond to what Shell were saying and doing or fight them in the courts. Now we can fight Shell on the same level and they don’t know what to do. (Vincent McGrath, Shell to Sea Campaign, interview with authors, June 2005)”

It is important to relearn our own hidden histories of struggle, they exist everywhere and can be uncovered. They can help to dispel apathy (‘it’s not worth it’) and powerlessness (‘it’s too overwhelming’). Learning these lessons show us that most of our freedoms and improvements, which we value in our lives today, have been fought for and won through collective and sustained action by people like ourselves, not great leaders. Oral history projects that engage with members of a community and record their memories and walks that visit sites of historical interest, of uprisings and old ways of life are two ways of relearning and connecting these forgotten histories.

3. Starting from daily reality

Any project should begin by looking for connections between problems and people’s everyday lives, not a preconceived idea of this reality. Popular education is about avoiding judging people and encouraging people to express themselves, in their own way. It is not about learning lists of facts, but looking at where people find themselves and how they understand what’s going on around them. Many believe that learning happens best where there is affinity between the educator and the participants – and when common experiences can be used as the material to be studied. In his work on popular education in the El Salvadorian revolution, John Hammond observed that the teachers in the National Liberation Front (an army largely made up of illiterate peasantry) were generally combatants who had only recently learnt to read or write themselves. The biggest challenge can be building bridges between disparate worlds. Talking about television or football and finding things in common can be ways to start a conversation. It takes time to connect with people, and respect and trust are the keys to positive learning.

4. Learning together as equals

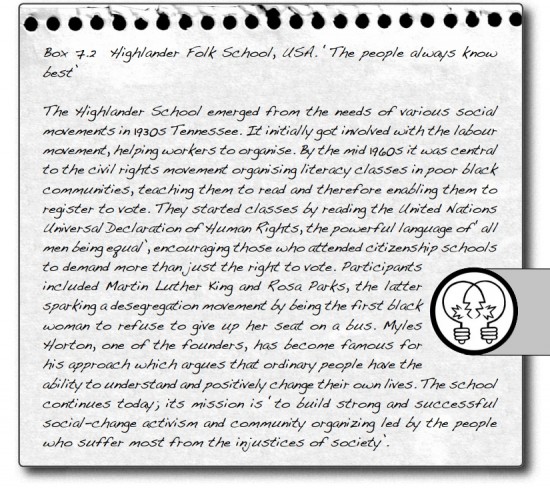

Popular education methods are designed to increase participation and break down the hierarchy between educator/teacher and participant/learner. The educators and those they are working with collectively own the process, ideally deciding the curriculum and determining the outcome of the action to be taken. Whilst in many contexts educators are seen as experts who can provide quick fixes, popular education has an explicit aim to reduce dependency between educators and those they engage with. Radical educator, Myles Horton, would tell his students at Highlander that if he gave them an easy answer today, what would stop them coming back tomorrow and asking him again? He argues that groups trying to find a way out of a problem are often the most capable of experimenting with possible solutions and should be encouraged to do so.

5. Getting out of the classroom

A critique of the powers and rules we live by cannot flourish when learning only happens within the official institutions and places controlled and funded by those in power. The state control of schools and compulsory education is not inevitable, nor does it reflect a widely articulated need. However, it has become all encompassing. The school forms the ideology, patriotism and social structure of the modern nation state. Free, compulsory education is now based on the assumptions that the state has the responsibility to educate all its citizens, the right to force parents to send their children to school, to impose taxes on the entire community to school their children and to determine the nature of the education on offer. One particular issue is the creeping influence of corporations on our education – through private academies, but also through sponsorship of learning materials, research, and even food and entertainment. Whilst we enjoy a ‘free education’ (i.e. we generally don’t have to pay) the influence of private corporations in the delivery of curricula as well as in schools’ facilities is increasingly a cause for concern. Teachers are ever more limited in what they can teach by the national curriculum, and there is more compulsory testing from a younger age. Students are taught conformity to values chosen by government and increasingly big business. A recent report highlighted the links between universities and the oil industry: Through its sponsorship of new buildings, equipment, professorships and research posts, the oil and gas industry has ‘captured’ the allegiance of some of Britain’s leading universities. As a result, universities are helping to lock us in to a fossil fuel future. (Muttitt 2003, 2)

Getting out of the classroom and institutionalised learning environments is a key part of rethinking learning about everyday life – outside encounters, street life, listening to somebody, at home, within the community are all places of learning that gives us valuable social skills and rounds our knowledge. This type of learning is also about challenging education’s negative associations and making learning passionate, interesting and challenging. People learn everywhere and using social

and cultural events, music, food and fi lm is a good way to reach out to people who may not come to a talk or workshop. Experiments in education beyond formal schools include ‘Schools Without Walls’, such as the Parkway Program in Philadelphia where the whole city was used as a resource.

6. Inspiring social change

Discussing important subjects, such as climate change, can be depressing and can leave us with feelings of despair and doom. Rather than avoid talking about them we can look at ways to deal with this. Firstly, we can identify a number of common barriers to changing attitudes or behaviour:

• Apathy, ‘I can’t be bothered’ or ‘It doesn’t affect me’.

• Denial that the issue exists.

• Feeling of powerlessness to do anything about the situation.

• Feeling overwhelmed by the size and scale of the problem/issue.

• Socio-economic time pressures and lack of support.

The way that learning happens can turn these attitudes around and help us turn our outrage and passion in to practical steps for action, our dreams in to realities. We can explore examples from the past where people have struggled and won and focus on workable alternatives. Practical tips for planning a workshop can help, such as identifying small achievable aims, breaking down issues in to manageable chunks, providing further resources, helping with action planning and campaign building.

Radical educators take on the responsibility to guide groups beyond common fears to reveal answers and possible escape routes to problems, laying possible options on the table. The art lies in the ability to make connections and establish bridges between people’s everyday realities and what they start to think is possible in the future. Hence, inspirations for social change are presented slowly and gradually, with honest reflection, compromise and setbacks along the way.

Part of this learning experience is about sharing what is feasible, both in the here and now and other times and places. There are many workable ways of living that directly challenge the money economy, wage labour and ecological crises – many of which are discussed in this book – working co-operatives, community gardens, low impact living, direct action, autonomous spaces, independent media. On their own they may not seem much and are spread far and wide. But if they are gathered up and presented collectively they can provide excitement and hope and form a basis for a more creative, autonomous life

Popular education in action

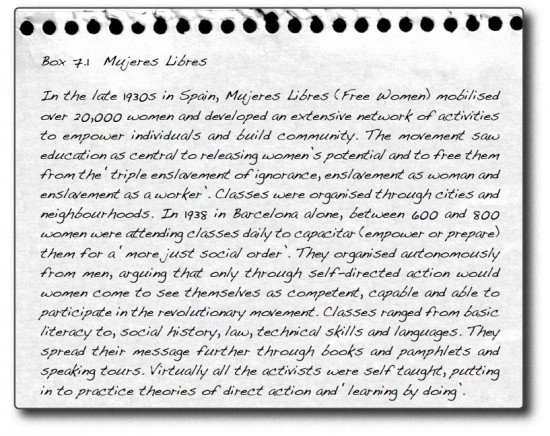

There is a rich history that criss-crosses the world as people have struggled for freedom and against oppression. Popular education has flourished at times of big social upheavals, when people question the way the world is, and see a need to change their lives.

Educating the workers for freedom

The Industrial Revolution meant massive changes and new realities such as overcrowding, long working days and urban poverty. Working-class people in the UK did not have the right to formal education; in fact many educators and members of the aristocracy argued that education would confuse and agitate working people. Various associations were established to campaign against this injustice. Some authorities conceded that education for working people might be useful so long as it was devoted only to basic skills development. Associations struggling against these views developed their own forms of education – ‘rag’ magazines, study groups and community activities. Socialists of various affiliations struggled to educate themselves and those around them to understand and tackle the horrific new realities of life, whilst openly trying to develop class consciousness.

The book The Ragged Trousered Philanthropist (1918) by Robert Tressell is one famous example. It depicts the efforts of Owen, a fi rebrand socialist painter, trying to educate his reactionary pals about the evils of capitalism. A rich tradition exists ranging from the Labour colleges, the Correspondence societies during the revolutions in France and the USA, to later experiments such as Co-operative colleges, Workers’ Educational Association, and adult education colleges such as Ruskin College in Oxford. Many of these presented a blueprint for transformation to a socialist society, based more or less on a Marxist-Leninist perspective. Alongside the workshop and the trade union, Marx schools or Workers’ universities were set up. These sprang up across the world into the twentieth century, offering classes to workers in the basics of socialist thinking whilst also training professional international socialist activists and agitators, and becoming a focus for anti-communist surveillance and repression. Radical organising in working-class communities has continued through tenants’ and claimants’ unions, and in the UK through anti-poll tax unions drawing on these powerful roots.

Free schools

Many educational alternatives have been tried over the years, experimenting with radical education through free or progressive schools. Many had revolutionary potential, not just undermining state power, but also challenging ways of life and were seen as a real threat. For example, Spanish anarchist Francisco Ferrer was executed for plotting a military insurgency when he opened a school that was free from religious dogma. The high point for free schools was the New Schools movement in Europe in the mid twentieth century. Schools were based on voluntary attendance and children and teachers governed the school together. There was no compulsory curriculum, no streaming, no exams or head teacher. Instead libertarian ideas were promoted and there was a focus on creative learning and interaction between different ages and the outside world. Free schools exist throughout the world, such as Mirambika in India and Sudbury Valley School in the USA. British examples include Abbotsholme School in Staffordshire and Summerhill in Suffolk. While education is compulsory, schooling isn’t; networks such as Education Otherwise and the Home Education Network provide support for the thousands of parents in the UK who choose to educate their children at home.

Struggles for independence

Popular education movements have played central roles in the struggles for independence in many colonised countries. In the twentieth century, socialist inspired nationalist struggles across Latin America and Africa used popular education to engage with the masses, challenge oppression, apartheid and colonialism. Liberatory educators in countries including Nicaragua, Granada, Cuba, El Salvador and South Africa set up educational programmes to mobilise the masses, especially the rural poor. In these revolutionary contexts popular schools flourished. ‘People’s Education for People’s Power’ in South Africa, for example, was a movement born in the mid 1980s in reaction to apartheid and was an explicit political and educational strategy to mobilise against the exploitation of the black population. It organised Street Law and Street Justice programmes and literacy and health workshops – these programmes were also subject to repression.

Latin America

One of the best known examples of popular education being used to challenge oppression and improving the lives of illiterate people is the work of Paulo Freire in Brazil. Working with landless peasants, he developed an innovative approach to literacy education believing it should mean much more than simply learning how to read and write. Freire argued that educators should also help people to analyse their situation. His students learned to read and write through discussion of basic problems they were experiencing themselves, such as no access to agricultural land. As the causes of their problems were considered, the students analysed and discussed what action could be taken to change their situation.

Radical popular education has recently seen a resurgence in Latin America, as people try to make sense of the current crisis brought about by 30 years of neoliberal economic policies. In Argentina after the 2001 economic crisis, Rondas de Pensamiento Autonomo (roundtables for autonomous discussion) and open platforms in neighbourhood assemblies have become common features where people talk about the crisis and possible solutions. The Madres de Plaza de Mayo (The ‘Mothers’ who tirelessly campaign against the disappearance of many innocent people during Argentina’s dirty war) have set up the Universidad Popular Madres de Plaza de Mayo on the Plaza del Congreso in the centre of Buenos Aires. This people’s university, dedicated to popular education, houses Buenos Aires’ best political book shop, the literary cafe Osvaldo Bayer, and gallery and workshop space which holds classes, seminars and debates on topics from across Latin America. Since the establishment of the Venezuelan Bolivarian Republic in 2001 under Hugo Chavez, Bolivarian circles and local assemblies have spread to engage people in implementing decision making and the new constitution.

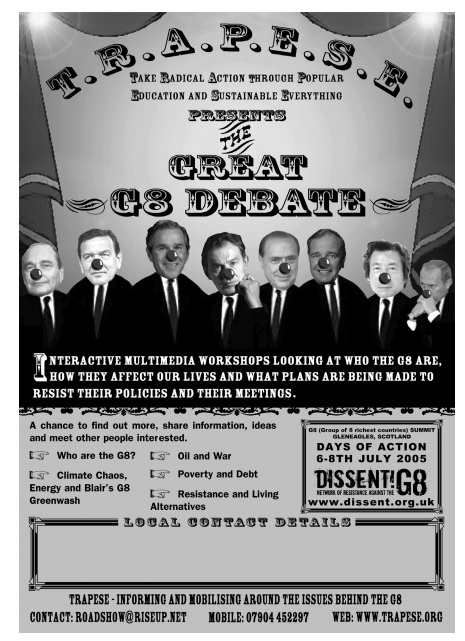

Education for global justice

Over the last ten years, the anti/alter-globalisation struggle has been a hotbed for popular education activity. A global summit of world leaders rarely passes without several teach-ins, counter conferences and skill sharing events where activists and campaigners come together to inspire and inform each other about what they are attempting to understand and challenge. Groups and networks have emerged dedicated to producing and disseminating a huge amount of information on topics crucial to understanding our contemporary world: sweat shop labour, fair trade, immigration, war and militarisation, the effects of genetically modified organisms, neocolonialism and climate change. Hallmarks of such workshops are teaching horizontally and encouraging equal participation. Whilst big campaigns and mobilisations are often times for such educational outreach there are many social centres that provide space for ongoing autonomous education. La Prospe in Madrid has, since the mid 1970s, hosted Grupos D’Apprendizaje Collectiva (Groups for Collective Learning) on topics such as gender, globalisation, basic skills and literacy. As well as converging at global summits there are many international gatherings and seminars that all provide means of exchanging, building and networking ideas and experiences of different groups.

Where now for popular education?

Social change will not be achieved by a small group but will involve bringing people together on an equal basis. One of the issues that has faced the alter globalisation movement is it’s need to communicate with aider audiences to get off the activist track. Although popular education on its own is not enough, it is one way for people to engage themselves and their communities in these discussions, to begin to think of their needs and possibilities that can be created.

In post 9/11 USA, Katz-Fishman and Scott argue that a climate of fear, hysteria and pseudo-patriotism has been created to control and contain dissent. they argue that:

“To prevent the fragmentation and break down of community means organising ongoing educational development among grassroots-low-income and student scholar activist communities of all racial-ethnic-nationality groups and bring people together on the basis of equality.”(Katz-Fishman and Scott (2003)

This, they argue, must be done ‘community by community and workplace by workplace’. We echo and support this call to action, to extend groups and networks of popular and radical education.

There is a widespread sense that something is not working. The illusion of infinite upward economic growth can’t be maintained for much longer as natural resources become scarcer and the capacity for the planet to absorb waste becomes exhausted. There is therefore, a potential for radical critiques to be articulated and developed. Popular education tools can help us do this in ways that make sense to people and to reveal why alternatives are possible and necessary. One great potential of popular education is that its participatory methods mean that ‘activists’ learn to make their ideas relevant and accessible. In a world where we all impact upon the lives of others, the boundary between who is the oppressor and the oppressed becomes increasingly confused. In the developed world, as consumers of the world’s resources driving a system of global exploitation, we must teach ourselves about the impacts we have on the world, the role our governments play, how to take responsibility, and, most importantly, how we can take action to change this. An education that seeks to address unequal power relations and empower collective action is vital. The work of people over the centuries, with limited resources but with a passion for change, should be our inspiration.

Popular education projects you can do

How to inspire change through learning

How things are taught is as important as what is taught in inspiring people to take action in their own lives. In these days of compassion overload we can’t assume that any shocking statistic or distressing story will have any impact. Instead we need creative ways to think and learn about the problems we face. In the year 2004–5 shortly after we formed our popular education collective Trapese, we carried out over 100 workshops, talks and quiz shows round the UK and Ireland exploring issues of the G8, climate change, debt and resistance. Since then we have continued our work exploring popular education methods as a way to support a range of campaigns. This chapter brings together practical advice which is based on our own experience of a four month long educational roadshow and from other groups who also use popular education as a tool for change.

Many of the activities and games mentioned in this chapter have been adapted from tried and tested methods of others doing similar work who made their resources available. What links the activities together is that they aim to create a collective understanding of problems, root causes and encourage people to take action, tapping into a desire for change. This is just a starter, there are many websites and books that expand all these ideas (see the resources box), but we believe that there is no better way to learn than by doing.

Getting organised

Here are some of the stages in organising an event.

(a) Knowing the subject

- Choosing the theme should be the easy part, remember to have a clear focus for the workshop. Local issues can quickly be scaled up and connected with bigger questions.

- Find out as much as possible about the participants – how often they meet, what their interests are, what level of awareness they may have about the topics you want to talk about.

- While you don’t need to be an expert, it’s important to have some concrete facts as they will help give you credibility and confidence. Use books, films and websites, newspaper clippings and quotes from the radio, TV and films.

- Research any existing campaigns and try to understand the arguments of all sides.

(b) Designing the workshop

- Running a workshop with more than one person can really help practically – it also gives more variety.

- Bear in mind that people normally retain more if they have an opportunity to discuss, question and digest. Less is more.

- Remember that there are neither correct answers nor easy conclusions. The aim of the activities is to plant the seeds of questioning and encourage people to find out more for themselves.

- Use a variety of different types of information – films, games, debates and allow free time for questions and informal discussion.

- Include plans for action and possible future steps early on. Things often take longer than you imagine and it’s depressing to hear all about a problem and then be left with no time to discuss what to do about it.

- Allow time for breaks – in our experience, any more than one and a half hours and people will start to switch off.

(c) The practicalities

- Getting people along can be the main challenge, look out for existing groups, unions, community groups/centres and spaces which have similar events.

- Advertise as early and as widely as possible using posters, websites, email lists, etc. but also think about personal invitations, which can be most effective.

- Set up all the equipment you need well in advance to avoid last minute stress.

- If space permits, arrange the chairs in a circle as people can see each other and there is no one at the front lecturing.

- Think of a method for people to give feedback and to exchange contact details.

- Provide snacks and drinks.

- Offer people the possibility of further sources of information, either through handouts or websites.

(d) Facilitating

- Keep to an agreed time frame and explain the aims and structure of the workshop.

- If you are friendly and respectful, then other people are more likely to follow your example.

- Make a brief group agreement at the start – this can include things like everyone will turn off mobile phones, agree to listen to other people speaking, wait their turn, etc.

- Ask people who haven’t spoken if they would like to contribute.

- Don’t be afraid to admit that you don’t know the answer. You can offer to find out or suggest that you find the answer together.

- People learn best when they come to their own conclusions. The facilitator’s role is to lead people through information, rather than presenting completed solutions. Ask questions and encourage participants to ask questions. For example, ‘the way it works is …’ can be replaced by ‘why do you think it works that way?’ This may take a bit longer but it is more likely to be absorbed.

- Use bright, colourful props and a range of media to draw people’s attention. Dress appropriately to the group.

Exercises for social change

Think of a really boring teacher at school. What made them boring? Were they monotonous, arrogant, bossy or stern? Think of some piece of information that really impacted on you. Why do you remember it? What struck you about it? How was it presented? Thinking about being a participant yourself will help you to plan a workshop. At the same time, remember people learn in different ways – through listening, writing, drawing, speaking and acting – so try and use a variety of senses. Many of these activities can be easily adapted to work on other topics.

1. Warm ups

Warm ups set the context of workshops and allow everyone to get to know each other. They can be more animated or calming depending on what you feel is appropriate for the group. Games can be a good way to create a participatory environment where everyone feels they can contribute. Some physical contact (being aware of different abilities and cultural sensitivities) can be a good way to relax people and break down personal boundaries. Go round the room and ask people to say their names, and if there is enough time ask them to add what they hope to get out of the workshop. This can help the facilitator pitch things accordingly.

Play a game:

Before you do anything, try playing a short physical game – we all know many from our childhood, such as musical chairs, keeping a ball or balloon up in the air, or stuck in the mud.

Finding Common Ground

Aim: An icebreaker and a way to see how many similarities exist in the group’s

Method: Everyone stands in a circle. Explain that when a statement is read out, if they AGREE they should take a small step forward. If they DON’T AGREE, stay put. No steps to be taken backwards.

Statements should try and reflect the interests of the group and controversial or topical issues. for example:

- ‘I think corporations are taking over our political processes’.

- ‘This makes me angry’.

- ‘I drink fair trade coffee/tea’.

- ‘I don’t think that’s enough’.

- ‘If more world leaders were women, the world would be a better place’ etc.

Depending on the size of the group, with ten or so statements everyone should be in the centre of the room. At this stage you can all sit back down again. Alternatively, ask each member of the group to close their eyes and put out their hands into the middle of the (now very small) circle. Ask each person to take two other hands. When they open their eyes the task is to untangle the knot of hands.

Outcomes and tips: The tangle is also good for working together out of an apparently impossible mess. Be prepared to abandon it if it takes ages!

2. Collective learning

Before beginning an explanation about collective learning, ask people what they already know about it. One way of doing this is to idea storm around an issue. Ask people to shout out what they know about something and write it up visibly so that everyone can see the ideas. Don’t correct people at the time if they say something incorrectly but make a mental note to come back to the point later.

Acronym game/Articulate

Aim: To jargon bust, build group understanding of terms and to gauge the existing knowledge of a group. The game introduces lots of background information and gets people working in teams.

Method: Write out some relevant acronyms or words on small cards. Divide the group into teams and divide the cards so they have roughly one per person. Ask groups to discuss the cards and work out what they are/mean/ do. Help if necessary. Each group then presents the acronym to the other groups without saying any of the words in the name. For example, if you have WTO you can’t say the words ‘World’, ‘Trade’ or ‘Organisation’ in your description but something like, ‘It’s a global institution that makes rules about and removes barriers to trade’. Or an emotional response, ‘It’s the most damaging institution in the world and should be abolished’. The team which correctly guesses what the acronym stands for receives the card.

Ask the group if they can explain the idea in more detail.

Some acronyms we have used include:

- PFIs (Private Finance Initiatives). Corporations investing in public services, such as hospitals and schools.

- IMF (International Monetary Fund). Lends money to developing countries; generally comes with conditions on market based reforms.

- WB (World Bank). Lends money to projects in developing countries, mainly focusing on large infrastructural projects like dams and roads.

- SAPs (Structural Adjustment Programmes). Conditions for IMF loans which involve liberalising the economy, deregulating and privatizing industries.

Outcomes and tips: Demystifying complicated acronyms and terms is important to developing a critical awareness about our world. This game can last a long time so be prepared to cut it short in order to stick to your workshop plan. Any words, names or ideas can be used for this game and it is a good lead in to the Spidergram game (see below).

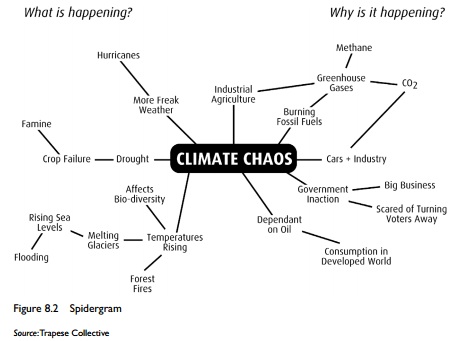

Spidergram (Mapping Climate Change)

Aim: To explore a topic visually, make connections between ideas and unpack cause and effect.

Method: In small groups, draw a box in the middle of a big piece of paper and write the big theme which you want to explore, e.g. ‘climate change’. Ask people to think of things which directly cause this like ‘fl ights’, ‘cars’ and connect these to the centre with a line. Then think of problems or issues relating to these issues like ‘pollution’, ‘asthma’, ‘traffi c jams’, etc. If linking to the acronym game, mentioned above, choose a couple of cards and ask people to draw connecters to other cards and arrange them.

Outcomes and tips: You’ll soon build up a picture of connections like a spider’s web.

Ask the group which words have the most links. Make sure you go round and help

3. Using visual activities

It is often more striking to see something simply but visually than to listen to a long list of statistics. Physical and visual activities change the pace and dynamic of a workshop, which helps participants retain concentration. Look for possibilities of involving practical tasks, training or experiments in the workshop.

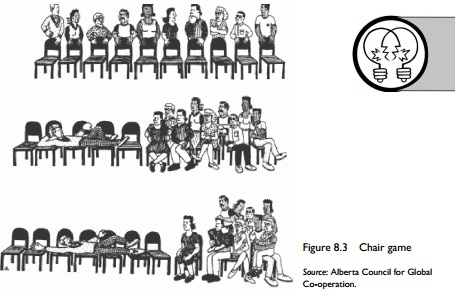

Chair game

Aim: A simple way to show the imbalance between the G8 countries and the rest of the world. This game can be modified to represent other imbalances or statistical information, e.g. debt, trade or carbon emissions.

Method: Ask ten volunteers to form a line with their chairs and to sit on them. You are going to ask a series of questions and in each question, one chair equates to 10 per cent of the total. During the game, people will move along the chairs according to their allocated amount. Always try to get the answers from the participants.

Explain that the ten people represent the world’s population, which is roughly 6 billion – so each person represents 10 per cent or 600 million people.

Question: What percentage of the world’s population is in G8 countries?

Answer: 12 per cent.

Nominate one person (ideally at one end of the line) to represent the G8. The remaining 88 per cent are the majority world.

Question: What percentage of the world’s total Gross Economic Output is produced by the G8

countries?

Answer: 48 per cent (roughly 50 per cent).

Ask the nominated G8 person to occupy five chairs while the remaining nine squeeze on to the other five chairs.

Question: What percentage of the world’s total annual carbon emissions are produced by the G8 countries?

Answer: 62 per cent.

Ask the nominated G8 person to occupy six chairs while the remaining nine squeeze on to the other four chairs.

Question: Of the top 100 multinationals how many have their headquarters in G8 countries?

Answer: 98 per cent.

That would leave the majority without any chairs but if the G8 generously gave a bit of aid that would leave them with one chair. Ask the nominated G8 person to occupy nine chairs while the remaining nine squeeze on to only one chair. This is obviously quite difficult.

Outcomes and tips: Ask the G8 how he/she is feeling – then ask the majority world

what they would do to change the situation. Some people might try to persuade the

G8 to give them their chairs back; others just go and take them.

4.Debate it!

Often participants really value an opportunity to talk freely, but as a facilitator free debate can be very difficult to structure and dominant personalities or viewpoints can easily take over. The following activities help to structure things.

The YES/NO game (or Issue Lines)

Aim: To see opinions in relation to other points of view and for participants to try and defend or persuade others of their perspective.

Method: All stand up and explain that you are all standing on a long line with YES at one end and NO at the other and NOT SURE somewhere in the middle. (It can help to make signs.) Read a statement and ask people to position themselves in the room depending on their point of view. When people have moved, ask someone standing in the YES or NO sections to try and explain why they are standing where they are, then ask the opposite side for an opinion. Allow the debate to continue awhile and then ask participants to reposition themselves depending on what they have heard.

Questions that we have used include:

- Is nuclear power a viable, alternative to fossil fuels?

- Is it desirable that levels of consumption in the developing world equal that of those in the ‘developed’ world?

Outcomes and tips: These debates are often lively. Be careful not to allow any one person, including the facilitator, to dominate and make sure the question has a possible yes-no range of answers. Try working in smaller groups to allow everyone to speak and then give time for groups to feed back their main points.

Role plays

Aim: To present different opinions and encourage people to think from varied perspectives. Role plays enable participants to develop characters and take on their opinions, providing an excellent opportunity to express common misconceptions and controversial opinions without the participants speaking personally.

Method: Prepare a ‘pro’ ‘anti’ and/or ‘neutral’ camp with prompt cards for each. This should include context, details on how to act and speak, and ideas on how to respond to questioning. Explain that people should keep in this role at all times, even if they don’t agree with the views expressed. Give people time to discuss and expand on the prompt cards. A good way to structure discussion is to chair a hearing between the different parties, where a mediator asks each side to present their case in turn. Allow time for open questions, followed by a summing up.

Example: Building a local road.

- Chief Executive of Gotham City: Your city is booming and the key to its success is road transport. Business and tourists are being attracted from the whole country. Argue that: if the new ring road doesn’t go ahead then the economic viability of the area will suffer. Less growth means fewer taxes, which means less money for public services.

- Concerned citizens near the proposed road: There has been so much development in this city that there doesn’t seem a case for any more. Roads are jammed already and just building more roads doesn’t solve the problem, but only encourages more car use. Argue that: more cars equals more pollution, accidents and unhealthy lifestyles.

Outcomes and tips: Role plays need to be well prepared and work best when people are confident speaking in front of each other. With a longer session, ask participants to research and develop roles for small groups to enact.

5.Connecting histories and lives

Sharing our collective pasts is a key way to begin to understand our present and to imagine our futures. There are many ways to do this, through oral histories, participatory video documentaries, etc. It can also be useful to plot events on to a visual representation of history.

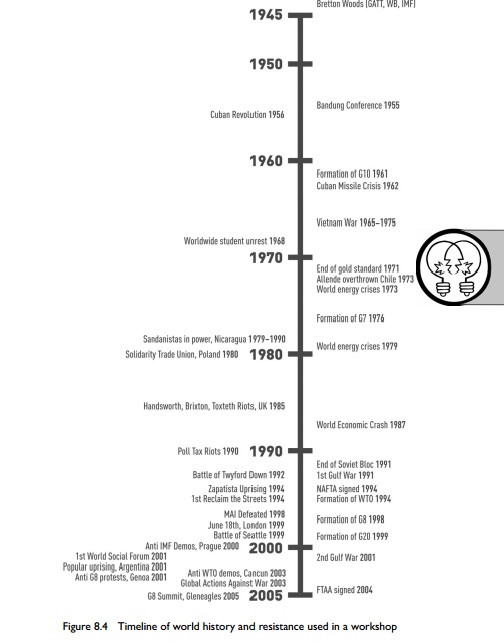

The rise of global capitalism and resistance timeline

Aim: To chart the rise of the current economic system and global resistance to it, to show international organisations in context. It can be used, for example, to show how US foreign policy has worked and evolved, or how resistance movements in the global North and South have progressed and connected.

Method: Draw a timeline on a big piece of paper or cloth, write key moments of the development of the economy and resistance events on to cards and give one or two to each pair. Give them time to discuss it and ask any questions about it and then ask them to put the events on the timeline where they think it occurred. Also give participants blank cards and ask them to fill in things they would like to add – maybe from their local area or that they have been inspired by. Go through the events, asking others to explain and give their opinions and help people identify connections.

Outcomes and tips: This activity helps people see connections between seemingly separate events. Make sure you have reliable information on dates, etc.

6.Get out of the classroom – creative educational events

Plays, film screenings, music, talent shows, bike rides, mural painting, nature trails, and cooking are all ways to get together and can be adapted to a theme. A walking tour can be a great way to bring a theme to life and to learn about our built environment or local history.

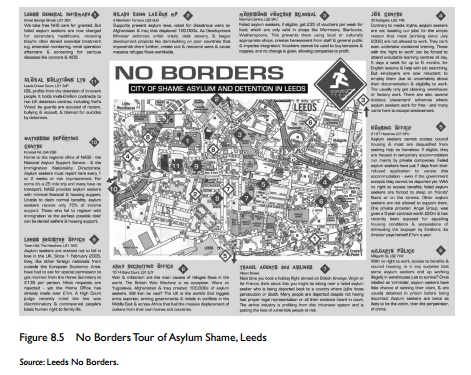

Walking tours of immigration controls and the ‘chain of deportation’

Aim: To draw to people’s attention institutions, companies and government departments involved in the chain of deportation of asylum seekers. A tour exposes the process and joins the dots in the picture of detention and deportation and helps understand the system.

Method: Research the government sponsored institutions and private companies that earn money carrying out these racist policies, and organise a tour to visit some of the places in your area that are involved in locking up and deporting asylum seekers. Go as a walking tour in groups, assemble in a public place and have easily identified guides with maps, information, loud speakers, music, etc.

Social change pub quiz

Aim: A social event where the content matter is related to important issues. Can be a good way to outreach to different audiences.

Method: Find a venue to host you – community centre, student union bar or a local pub – and advertise the event. Make up several themed rounds of questions, get answer sheets, pens and prizes and maybe a microphone. Keep it varied by using multiple choice, picture or music rounds, bingo or maybe even some subverted karaoke.

Example: The Food Round.

1. How many million battery chickens are produced for consumption each year in the UK? (Answer: 750 million)

2. How many billion did Wal-Mart’s global sales amount to in 2002; was it (a) $128 billion, (b) $244.5 billion, or (c) $49 billion? (Answer: b)

3 What is the legal UK limit for the number of pus cells per litre of milk that may be legally sold for human consumption? (Answer: Up to 400 million)

Sources: 1. and 2. Corporate Watch (2001) 3. Butler (2006).

7. Planning for Action

The aim of the game is that people leave with concrete ideas about what they are going to actually do – a next date, an ambition or a vision. This stage is also a chance for people to share ideas about the things they are already doing and plug any events or projects.

Action mapping

Aim: To show a variety of actions and inter-connections.

Method: Ask groups to think of two ways to tackle the issue that the workshop is dealing with at different levels: the individual, local and national/international for example.

Outcomes and tips: Get groups to think about time scales for their actions and how they practically might do them. A variation is to think about two things to do this week, this month, this year, etc.

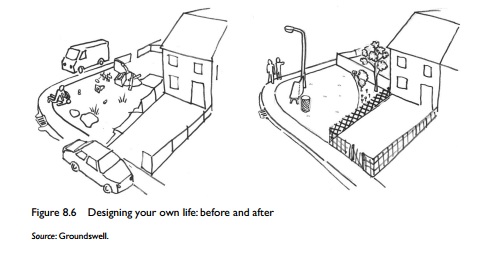

Picture sequences

Aim: To look at how things are and how we would like them to be, and to work out how to get there.

Method: Draw a simple picture that represents, ‘the present’, with all the problems illustrated. Then, as a group, put together a second drawing to represent ‘the future’, which shows the same situation once the problems have been overcome or the improvements made. Make sure you incorporate everyone’s ideas of what you hope to achieve. Once you have the drawings, put them where everyone can see them with a space in between them, then ask yourselves how you can get from the first to the second. What needs to happen to get there? How could it be achieved? Use the answers to make your own middle, between the present and the future. Now you have your vision and have gone some way to working out your action plan.

Presents

Aim: To end the workshop on a high note and to get participants to ‘think the impossible’.

Method: Identify the main problem that people want to focus on. Give out cards with an imaginary present written on to each participant. Ask them to describe how they would use their present to solve the problem.

Examples:

- the ability to look like anyone you want

- £1 million

- a minute of prime time TV

- a key that unlocks any lock

- an invisibility cloak

- a guarantee you’ll never get caught.

Calendars of resistance

It’s important to share information on other things that you know are going on in the area. Draw up a calendar with contact details for people to get more information.

Skills for good communication

- Challenge dominance. Both from vocal participants and as facilitators. Be open from the start about why activities are being undertaken and do not manipulate participants to certain ideological ends.

- Don’t judge. Be supportive in your approach and recognise the validity of a diversity of actions and viewpoints. It’s not about persuading people to think or act as you want them to!

- Listening is crucial. Learn the importance of active listening to allow necessary discussion. Letting people talk, reducing dependency and empowering people to think for themselves are at the heart of radical education.

- Overcome powerlessness. If everything is connected you can’t change anything without changing everything. But you can’t change everything, so that means you can’t change anything!’ (A student after a lesson on globalisation from the book Rethinking Globalisation) (Bigelow and Peterson 2003).

While it’s not true that we cannot change anything, this student’s comment demonstrates how depression and a feeling of powerlessness is a logical reaction when solutions seem very small in the face of such large forces. Here are some tips for giving positive workshops about negative subjects:

- Don’t cram in too much information. Go step by step and give things time and space to develop. Mention the empowering side. Look for the positive things we can do and emphasise our creativity, our adaptability. Sharing personal experiences and failures can be very useful. Start with concrete achievable aims and develop from there.

- It is important that people are not left feeling isolated and that there is follow up.

- Try making a presentation about initiatives or protests that have inspired you with images or photos and use this is a springboard for talking about the viability of these ideas.

Making the leap to action

There are lots of issues which people are angry and passionate about and areas where they want to take action. Getting together to discuss and understand problems is a good way to reduce feelings of isolation and to launch campaigns and projects. It is really important to pick our starting points carefully, to build up trust and meet people in their daily realities, whilst not being scared of expressing radical views. Having worked with different groups we have been continually inspired by people’s views, opinions and desires to instigate change. These experiences have helped us to break down the false distinction between activists and everyone else and we have learned as much as we have taught. Popular education is about building from the beginning and finding innovative ways to learn together, realising the capacity that we have to take control of our lives and facilitating collective action, and for us, this lies at the heart of building movements for change.

Popular Education Articles

Loads of great free Popular Education Resources from the Catalyst Centre.

Commeuppance Thoughts on popular education, storytelling and activism for a possible better world

Informal Education Project Great site with loads of articles, links specialising in the theory and practice of informal education, social pedagogy, lifelong learning, social action, and community learning and development.

http://comeuppance.blogspot.ca/2009/08/popular-education-and-diverse-economies.html

Popular education films

Liam Kane from the University of Glasgow speaks about his interest in the area of popular education and how the Pink Tide represents exemplary lessons for the rest of the world to learn. Liam presented an interactive session on popular education at the Pink Tide conference. The conference was hosted by the Centre for the Study of Social and Global justice, based in the School of Politics and International Relations.

Anarchist and Popular Education from Burning Hearts Media on Vimeo.

Panel discussion on ‘Anarchist and Popular Education’

What is Popular Education? from Gilda Haas on Vimeo.

The aim of Encuentro is to bring together approximately 50 – 75 educators, academics, students and activists with an interest in popular education theories, methodologies and practices. This Action Chronicle presents some of the happenings of the two-day gathering that served to share popular education praxi.

How can we have meaningful participation when decision making is in the hands of the few?

Dr Eurig Scandrett knows that “popular education is about a dialogue”. He’s studied education systems in communities affected by pollution and other environmental injustices.

“What formal education does is give certain groups of people the power to select the knowledge which is supposed to be good for, usually, young people,” he argues. His conclusion is that the non-participation of groups affected by the outcomes of decisions leads to an unhealthy democracy.

Dr Scandrett’s solution is an education system where participants negotiate what is taught — and where people teach from personal experience.

Some individuals are going further. Tired of the shackles of a force-fed syllabus, they’ve decided to hack their own education — so called hackademics.

Do we have the right to call ourselves a democracy when very few people have a proper say? Is formal education failing citizens and leading to an unhealthy existence?

Part 1 Judith Marshall and Rita Kwok Hoi Yee, two Popular Educators share their stories and thoughts on the theory and aspects of Popular Education

Patricia Hernandez – Popular Education in Zapatista Indigenous Communities

Popular Education Strategies

Pedagogy of the Oppressed: Noam Chomsky, Howard Gardner, and Bruno della Chiesa Askwith Forum On Wednesday, May 1, the Askwith Forum commemorated the 45th anniversary of the publication of Paolo Freire’s “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” with a discussion about the book’s impact and relevance to education today.

Analysis of Paulo Freire Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

Short documentary about Paulo Freire. Seeing Through Paulo’s Glasses: Political Clarity, Courage and Humility Directed and Produced by Dr. Shirley Steinberg, and Dr.Giuliana Cucinelli

Paulo Freire and Ubiratan D’Ambrosio / English

—————

There are loads more videos on Popular Education and Paulo Friere online, just search youtube and google.

Resources: Books

Books

General

Acklesberg, Martha (1991). Free Women of Spain, Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women. Edinburgh: AK Press.

Bigelow, B. and B. Peterson (2003). Rethinking Globalisation. Rethinking Schools Press, USA.

Buckman, P. et al. (1973). Education without schools. London: Souvenir Press.

Butler, J. (2006). White Lies – Why You Don’t Need Dairy Talk. London: The Vegetarian and Vegan Foundation.

Carnie, F. (2003). Alternative approaches to education: a guide for parents and teachers. London: Routledge.

Corporate Watch (2001). What’s Wrong with Supermarkets. Oxford: Corporate Watch.

Crowther, J., I. Martin, and M. Shaw (1999). Popular education and social movements in

Scotland today. Leicester: NIACE.

Crowther, J., I. Martin, and V. Galloway (2005). Popular education. Engaging the academy. International Perspectives. Leicester: NIACE.

Katz-Fishman, W. and J. Scott (2003). Building a Movement in a Growing Police State. The Roots of Terror Toolkit, www.projectsouth.org/resources/rot2.htm

Freire, P. (1979). Pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Penguin.

Freire, P. (2004). Pedagogy of indignation. London: Paradigm.

Giroux, H.A. (1997). Pedagogy and the politics of hope. Theory, culture, and schooling: a critical reader. Colorado: Westview Press.

Goldman, E. (1969). ‘Francisco Ferrer and the Modern School’. In Anarchism and Other Essays. London: Dover. 145–67.

Goodman, P. (1963). Compulsory miseducation. New York: Penguin..

Gribble, D. (2004). Lifelines. London: Libertarian Education.

Hern, M. (2003). Emergence of Compulsory Schooling and Anarchist Resistance. Plainfi eld, Vermont: Institute for Social Ecology.

Hooks, B. (2004). Teaching community. A pedagogy of hope. London: Routledge.

Horton, M. and P. Freire (1990). We make the road by walking: conversations on education and social change. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Illich, I. (1973). Deschooling society. London: Marion Boyars.

Koetzsch, R. (1997). A Handbook of Educational Alternatives. Boston: Shambhala.

Muttitt, G. (2003). Degrees of Capture. Universities, the oil industry and climate change. London: Corporate Watch, Platform and New Economics Foundation.

Newman, M. (2006). Teaching Defi ance: Stories and Strategies for Activist Educators. London: Wiley.

Ward, C. (1995). Talking schools. London: Freedom Press

Free schools

Gribble, D. (1998). Real Education. Varieties of freedom. Bristol: Libertarian Education. .

Novak, M. (1975). Living and learning in the free school. Toronto: Mclelland and Stewart Carleton Library.

Richmond, K. (1973). The free school. London: Methuen.

Shotton J. (1993). No master high or low. Libertarian education and schooling 1890–1990. Bristol: Libertarian Education.

Skidelsky, R. (1970). English progressive schools. London: Penguin.

Popular histories

Hill, C. (1972). The world turned upside down. London: Maurice Temple Smith.

Morton, A.L. (2003). The People’s History of England. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Thompson, E.P. (1980). The Making of the English working class. London: Penguin.

Zinn, H. (2003). A people’s history of the USA. London: Pearson.

Resources: Websites

Websites

Catalyst Centre www.catalystcentre.ca/

Centre for Pop Ed www.cpe.uts.edu.au/

Development Education Asociation www.dea.org.uk/

2002 Education Facilitators Pack www.web.ca/acgc/issues/g8

Education Otherwise www.education-otherwise.org/

Paulo Freire Institute http://www.freire.org/

Highlander School www.highlandercenter.org/r-b-popular-ed.asp

Home Education www.home-education.org.uk

Institute for Social Ecology www.social-ecology.org/

Interactive Tool Kit www.openconcept.ca/mike/

Intro to Paulo Freire www.infed.org/thinkers/et-freir.htm

Intro to Pop Ed www.infed.org/biblio/b-poped.htm

Laboratory of Collective Ideas (Spanish) www.labid.org/

PoEd News www.popednews.org/

Popular Education European Network List http://lists.riseup.net/www/info/poped

Popular Education for Human Rights www.hrea.org/pubs/

Practicing Freedom, popular education training http://www.practicingfreedom.org/offerings/popular-education/

Popular Education Handbook download http://208.89.55.99/devel/wp-content/uploads/A_Popular_Education_Handbook.pdf

Project South www.projectsouth.org/

Toolbox for Education and Social Action http://store.toolboxfored.org/

Trapese Collective www.trapese.org

Film resources Beyond TV www.beyondtv.org/

Big Noise Films www.bignoisefilms.com/

Carbon Trade Watch www.tni.org/ctw/

Eyes on IFIs www.ifiwatchnet.org/eyes/index.shtml

Global Exchange http://store.gxonlinestore.org/fi lms.html

Undercurrents www.undercurrents.org/

A big thanks to the Trapese Popular Education collective for allowing us to reprint their overview of popular education. The Trapese Popular Education Collective is Kim Bryan, Alice Cutler and Paul Chatterton.They are based in the UK and since 2004 have been working with groups of adults and young people to understand and take action on issues including climate change, globalisation and migration. They also produce educational resources and promote participatory, interactive learning through training and skill-shares (see www.trapese.org).